How Making 'Boys Go to Jupiter' Was Like Carrying a Million Little Pebbles

Director Julian Glander discusses aging, musicals, and animation with Albert Birney.

Hello! Hope you’re having a great Labor Day weekend. If you’re not, things are about to turn around. Today in the newsletter we’ve got a very special conversation between two kings of DIY animation: Julian Glander, who directed Boys Go to Jupiter (in select theaters now!), and Tux and Fanny creator Albert Birney. Glander and Birney met at SXSW in 2017, and have remained friendly ever since. When Glander was finishing Boys Go to Jupiter, he sought advice from Birney. Here, the two have a fun and enlightening catch-up, touching on everything from band life to their feelings on aging and unhealthy Letterboxd habits.

TIDBITS

News and Notes

The 2025 Gotham Week Expo will be Sept 29 - Oct 3, in Brooklyn and Manhattan. Programming info was released last week here.

The market for film acquisition has been notoriously bad the past couple years. But there’s a small bit of good news for some of the best undistributed features. Per Indiewire:

The Popcorn List — a survey of acclaimed (but still undistributed) feature films that debuted at major or regional film festivals over the past year and come highly recommended by festival programmers — is already taking a big step forward. Next month, the creators of the list will host various pop up screening events, both at theaters and virtually, to show off the very same films they’ve been championing.

Get tickets and see the lineup here.

Park Chan-wook’s No Other Choice seems to be the front-runner to win Venice and there’s buzz coming out of Telluride about Jesse Plemons’s performance in Bugonia.

The New Yorker has a good feature story on the history and present state of A24 as the company navigates what seems like an inflection point — making bigger films, which demand bigger returns; expanding beyond film; experimenting with AI.

A24 has long tried to strike a balance between originality and marketability. “Under the Skin,” Glazer’s film, was a turning point for the company. Although its box-office performance was weak, it put A24 on directors’ radars as a place that took artistic risks. The brand is inextricably linked to such daring. But, as an early employee told me, “It’s harder for them to do ‘Under the Skin’ now. I don’t think they would do it, personally. So they’re at this point of: Can they bring their audience with them? Does their audience want them to go to that place?”

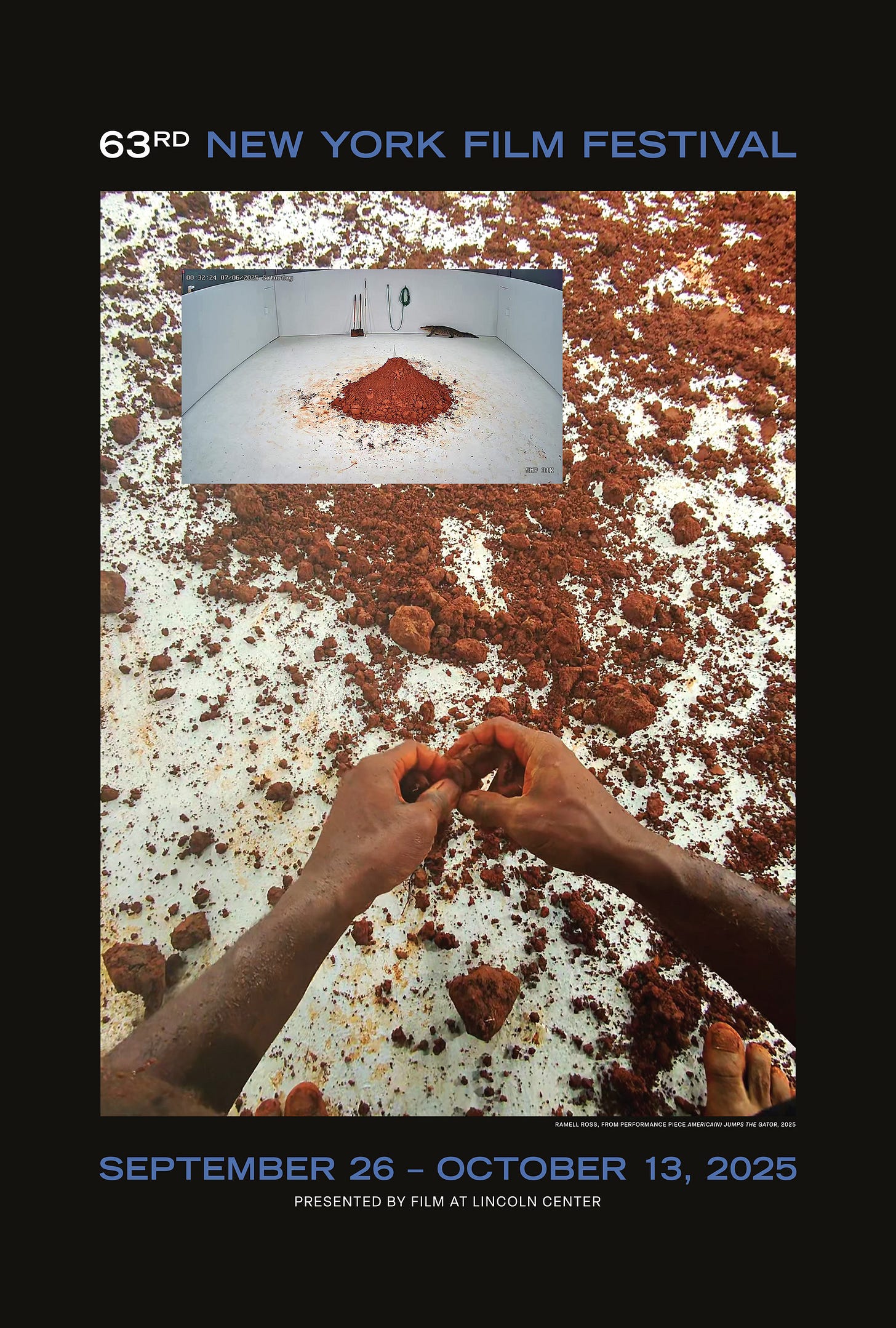

NYFF unveiled its 2025 poster last week. It was designed by Ramell Ross, who said of his inspiration: “the poster consolidates two ontological image perspectives, one from point of view and another from a security camera, both from my 24-hour performance piece, America(n) Jumps the Gator. As the New York Film Festival acts in many ways as an expression of our times, the language of the poster sprouts from the idea of photograph and film as an almost spiritual, meta mode of knowledge production, not unlike a spell, prayer, medicine or poison, or piece of legislation, though, as ineffable as the sensation of deja vu.”

SCREENING OF THE WEEK

September 7 @ 7:00 PM: “A Night of Fashion on Film”

I’ll be out of town Sept 7, but if I weren’t, I’d be at a night of fashion short films hosted by Eddy Frumkin at Life World. Program and ticket link here.

THE FEATURE PRESENTATION

How Making 'Boys Go to Jupiter' Was Like Carrying a Million Little Pebbles

Director Julian Glander discusses aging, musicals, animation, and more with Albert Birney.

by Albert Birney

A few weeks ago I had the pleasure of talking with my friend Julian Glander via Zoom. He was in Los Angeles promoting his remarkable animated feature film Boys Go To Jupiter. The film is a hilarious look at a group of young friends in suburban Florida who hang out on the beach, deliver food around town, and sing catchy musical numbers that you will find yourself singing long after the movie is over. It’s a unique and visually stunning adventure that is animated in Glander’s trademark “squishy” 3D style. In our conversation we covered a wide range of topics, including what he was like as a child, aging, the internet, musicals, and how he animated a full length feature film entirely on his own.

Julian Glander: We first crossed paths at SXSW 2017. I don't know if we met, but you saw my film and I saw your film. And that's when we started chit-chatting.

Albert Birney: Yeah. Yours was in the animated shorts program, which I was really excited to see. I always try to see animated shorts at festivals, because that's where all the weird, good stuff is. But yeah, it's nice when you feel a kindred spirit out there in the world doing things where it's like, "Oh, I think I know this person a little bit" just based off of their strange artistic brain.

JG: Then I did my deep dive and realized you've touched so many things that are so important to me. The Perry Bible Fellowship, The Spinto Band… I feel like you're the Forrest Gump of this really specific, 2000s twee thing that was so important to me.

AB: It's funny because I have done many things over the years, but most people don't know that. But every once in a while there's someone like you who's like, "I can't believe you were in this obscure band." It's usually people like you who are a certain age and —

JG: Freaks.

AB: Freaks who were online at the beginning of that phase of the internet.

JG: We didn't know how good we had it.

AB: I don't know if you've experienced this but over the past few months I've googled a restaurant, like "What's a good Thai restaurant in this area?" and the first results come up and they're the dreaded AI results and it's like, "Good question. To find out what the best Thai restaurants are, that's something you could google." And you're in this crazy feedback loop. I remember when Google used to be a place where you could find answers. And it's harder and harder these days. You slowly slip into that old man, "Back in my day..." thing.

JG: But I don't think young people think the internet is good in the way I remember being a teenager and being like, "The internet is a special place that's like a garden that I go to for an hour every day, and it's good even though there's a lot of weird stuff on it." I think most people see the internet as a really invasive force in their life that they're stuck with.

AB: That shift happened quietly.

JG: We all bought into it. That's kind of what the movie is about. How willingly we gave up some of these promises of freedom in exchange for a very shiny, gamified version of reality.

AB: And you're like, "How to get back?" But maybe that was never there. And maybe the best answer is to go to the beach with your friends and poke weird sea creatures in the sand or something. But, hey, let's talk about the movie.

JG: Fine.

AB: Last we talked you had just finished it up and were figuring out how to get it out into the world. Now you've successfully figured that out. So what's it been like having it out?

JG: Yeah, last we talked I called you and said "I don't know what to do. We finished a festival. I don't know what happens next." And your advice was to let it play at festivals, meet the people at festivals, show it to as many people as you can. And we did a year of festivals — basically a festival every weekend for the past year. I think we've had 45 of them. I didn't get to go to too many of them. But I was perversely checking in on Letterboxd to see how everyone was taking it.

AB: I love that. I'm in a similar year long stretch now [with my new film, Obex]. And you don't get to go to them all, but you always can tell when it played somewhere because you get a little blast.

JG: I have to get off Letterboxd. The power of a negative review — when someone needles me a little, it's like I need to get ten more good ones to get the taste out of my mouth.

AB: I always think about how my favorite film is someone else's least favorite film. You didn't make it to please everyone.

JG: Yeah. The people who have really taken umbrage with the movie want something out of it that I'm not interested in delivering.

AB: I don't know if you do this, but I'll go and check their top four.

JG: Every time someone really trashes the movie, La La Land is in their top four. Every time.

AB: It stings more if something in their top four is something you really love. But what I do love about Letterboxd is it's kind of the closest thing to a video store, where you can browse. If I find someone and I really like a review they wrote, I'll go click on their watchlist and you can get in these little worm holes of finding out about new films, great posters...

JG: And overall, it's really enriching when someone engages with the movie. Reading a thousand Letterboxd reviews has helped me understand the movie and I think it's helped me understand myself a little better. It's free psychoanalysis. I haven't seen Obex, but it seems like you're always trying to work out a lot of stuff in yourself on the screen.

AB: Totally. And there are those reviewers who say "This person needs to go to therapy instead of making a movie." And that's fair. But I do love when you read a good review and you're like, "Oh, that's what I was working through." But you mentioned La La Land, a contemporary musical. Obviously Boys Go to Jupiter is a musical. Did you grow up watching musicals? What's your relationship to the genre?

JG: I don't think of myself as a musical fan. I'm not sure I've ever gone and seen a musical as an adult. I don't keep up with them. But at the same time a lot of my favorite movies are musicals. And I love that it's a widely accepted format to do some of the most bonkers storytelling and visual stuff. In a totally mainstream story we can cut to a music video for two minutes. One touchstone would be Greece. There's a lot of intertextuality between Boys Go to Jupiter and Greece. In some ways I see it as a 2000s version. You have these kids who don't quite act like kids. And there's no adults around. And it's a lot of 30-year-olds playing high schoolers. But what I loved about Greece was the specific sonic palate. It's like, "We're going to do the '50s." And for me, I wanted to do the suburban Florida the way I remember it — this hazy, dreamy thing. If the main character is in his garage, this is what it would sound like.

AB: When you were writing the songs, did they come after you'd written the script?

JG: They're kind of bridges between the different parts of the story, so they were really useful building blocks for the script. There's only so many silly transitions you can do between scenes. There was so much of the script where I wanted to leave things open-ended during production. Which is something you can't do when you have financing. But for me that was important. I needed stuff coming later where I could be completely inventive and creative so I'm not just putting together Ikea furniture or a Lego set that I set up for myself. So the music came in pretty late in the process, and it changed a lot as the cast came on. Mia's song is obviously very beautiful and it's kind of the shimmering, textural centerpiece of the movie. And then Billy's songs are really great because they sell his character. And Grace's song is so funny and her voice is so good.

AB: I love your visual style, I love the comedians and everyone you got, but the music is totally this glue that helps me flow through the movie. It's really catchy. I know you've always done music. Was there ever a point in your life when you were like "I'm going to do music more than the visual stuff"?

JG: It's how it all started. My producer, Peisin [Yang Lazo], and I were in a band together in the early 2010s, doing the New York thing. I had the dream. I was playing the guitar and singing. I was like, "I'm going to be in Nylon Magazine. We're going to get our picture taken and be a cute little indie band." And it so did not materialize. I wasn't much of a songwriter. I couldn't make anything stick together because I didn't really have anything to sing about. When I started doing music for animations it made so much more sense to me. It was like, "This is a place music can go and be doing something and doesn't have to be just ‘Baby, baby, I love you.’" That was my full understanding of what a songwriter could be. I wanted to be a poetic person. A mopey, thoughtful, introspective singer-songwriter. And I'm not. But in some ways this movie is me and Peisin's revenge. It's our chance to make people listen to our music.

AB: With music, unless you reach a certain level and get the support around you, it's definitely a younger person's game.

JG: One thing I like about being a filmmaker is you can be young for a really long time. They're talking about PT Anderson like he's still a young hotshot. He's like 90. So I'm settling into something nice here.

AB: But when you remember he made Boogie Nights when he was like 27, you're like, "Oh, right, OK..."

JG: Thinking back, I felt so old when I was 23 because I kept looking at these geniuses who had success right away. Girls was on TV and I was like, "If I'm not running a hit HBO show by the time I'm 25 this was all for nothing. There was no point." When you get older, that stuff passes by you. You're someone I really look to who's found a sustainable way to do this that's not, "I have to have a big hit when I'm 22 or I'm done for."

AB: I think it's looking at the big picture, the long game. I'm just going to keep making things. And if I can make a film a year or every couple years, it's a body of work. It adds up. And if some kind of bigger success ever comes maybe there will be this looking back.

JG: We'll have the big retrospective at the Guggenheim where you're walking up the spiral. You just reminded me — we haven't talked in a while about Tux and Fanny, and how instrumental that was for me in understanding what a feature film could be. Even hearing about the way you made it.

AB: That was one of my questions. Was it always in your head that you were going to do Boys Go to Jupiter this way or was there a point where you thought you had to find funding or find a team of animators to do this?

JG: I knew there wasn't going to be funding for this kind of project. Or if there was funding, it would take so long that it wouldn't materialize. Before I knew it was a movie I knew what the story was. I knew I wanted to do something about delivery drivers. I'd been keeping notes on them and writing out different scenes. This could've turned into a show or a video game but it felt right to do it as a movie.

But when you talked about how you'd do one segment of Tux and Fanny a week and then connect them into that 90-minute thing over the course of two years, it broke my brain open. A movie isn't like carrying a big, heavy rock; it's like carrying a million little pebbles. I can't carry a car across the street, but I could maybe take it apart and carry it down the street and rebuild it. And thinking of it as something you continuously chip away at is one of the best things about animation. The fact that it's purely time put into it equals output in some equation.

AB: Knowing that it worked for you and that you put your car together and are now driving it all over the country, do you have your eyes set on another car?

JG: [laughs.] Yeah, we may have this in common — it's very important for me to do new things or do things in a new way. I've been thinking a lot about what a different way of doing an animated movie would be. I'm kind of hoping to find some documentary subject where I can have someone talk to me for a few hours and then build a movie around them. I love working with documentary audio. But I'm quite superstitious about new projects.

AB: Give me a little bit of a picture of you as an eight year old? Were you a creative person?

JG: I think I didn't start thinking of myself as a creative person until much later. I thought of myself as much more of an analytical person. I was into this idea of science where it's like, "I'm going to do a science experiment." And it's always like food coloring and soap going together. I was really into that kind of stuff. And I really liked being alone. We lived in Georgia and we had some woods in the back of our house and most of my memories from that time are being in the woods. Creatively what I was into was Legos. I think working with Legos is obviously so much like working in 3D. And like what we were talking about before, it gets at this idea that everything is made of little pieces.

What about you? You have Obex. It's doing really well. When will it be in theaters?

AB: January, 2026. Oscilloscope is putting it out. We haven't talked too much about where yet. That whole project came about because Kentucker [Audley] and I are trying to get our follow-up to Strawberry Mansion done and it's been years. We wrote it and then you're casting it and fundraising. It's all good but then months and years slip away. As I got older I realized I need a couple projects in various forms happening. When you put your eggs in one basket it's like, "What is my life if this one thing goes away?"

JG: Something I've tried to learn from you is it's very easy for filmmakers to live in a wait-and-see culture where they're living from meeting to meeting or development milestone to development milestone. And obviously one of the keys to your success is the way you're able to fill time in between all these things you have to wait for.

AB: When I was teaching film something I'd tell my students was, "We all have these huge dreams and we'd all love a blank check. But in the meantime what can you be doing with people around you or even by yourself? What fun can you make for yourself so that you're not just sitting around twiddling your thumbs?" All these projects are kind of just ways to play make believe with my friends — to get to travel and be a kid trying to amuse myself.

JG: We're talking like we're the oldest people on the planet. We've seen life from every side. And we probably have another thirty years of this. So we need to reflect on this talk in fifty years and be like, "Were we onto something there or were we being a little too wistful?"

Albert Birney is a Baltimore based filmmaker. He has directed six feature films, The Beast Pageant (co-directed with Jon Moses), Sylvio and Strawberry Mansion (both co-directed with Kentucker Audley), Tux and Fanny, Eyeballs in the Darkness and OBEX. Sylvio was named one of the ten-best films of 2017 by The New Yorker. His films have premiered at Sundance, SXSW, the Maryland Film Festival, Slamdance and the Ottawa International Animation Festival. In 2021 he released a Tux and Fanny video game that he made with Gabriel Koenig.

JOBS, PROGRAMS, AND OTHER OPPORTUNITIES

The Listings

Alek Abate is seeking male actors between the age of 18 and 23 for a Florida-set Columbia MFA short film, shooting in November. Email alldayisalongtime@gmail.com to learn more.

Kate Lopez is looking for someone to do sound for a feature pickup shoot 9/7. Paid. DM @katereneelopez on IG.

Jinho Myung is looking for extras for shoots 9/5, 9/6, 9/7, 9/9/, and 9/15. Only a few hours. Snacks, light vibe, credited. Sign up here.

Future of Film Is Female just announced its 2025 Shorts Program at Nitehawk. September 17, at 6:30 PM and 9:15 PM. Get tix now.

Recently, I created this spreadsheet for producers to consult when seeking crew, gear, or scripts to develop. If you’re looking for work or to find collaborators, sign up. It’s free.

If you would like to list in a future issue, either A) post in the Nothing Bogus chat thread, or B) email nothingbogus1@gmail.com with the subject “Listing.” (It’s FREE!) Include your email and all relevant details (price, dates, etc.).