Life World 1.0 → Life World 2.0

A short oral history of one of Brooklyn's most special spaces.

Hello, and welcome to Nothing Bogus! Today (okay, tomorrow) is my birthday. And you bet I’m going to use that as an excuse to shamelessly beg you to upgrade your subscription to a paid one and/or share this newsletter far and wide. Seriously, I will be so grateful.

RESOURCES

If you’re a filmmaker, producer, or crew looking for work or collaborators, check out this post and add your info to the Nothing Bogus Directory.

SPACES, PLACES

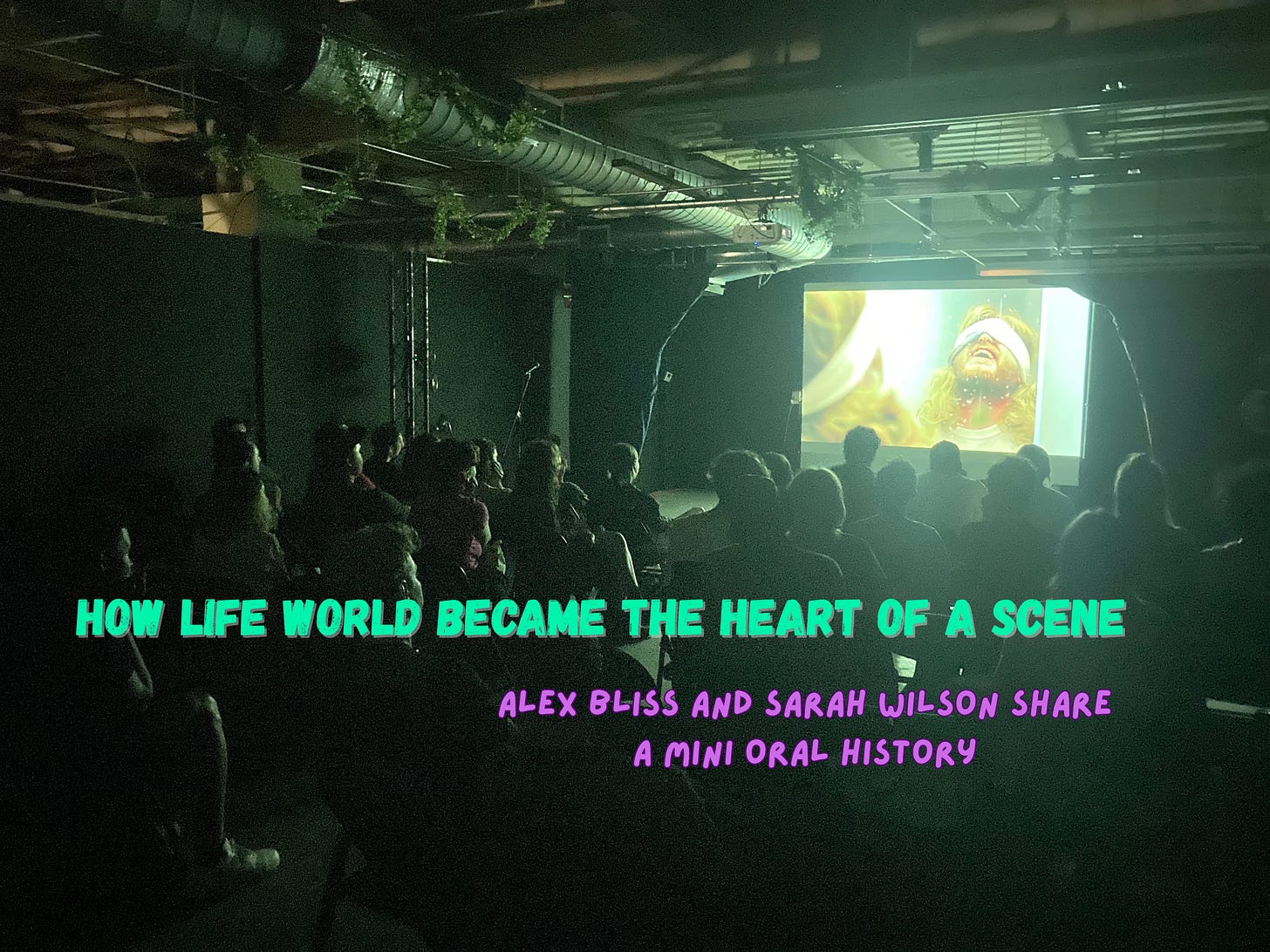

How Life World Became the Heart of a Scene

Founders Alex Bliss and Sarah Wilson give a mini oral history, reflecting on what made the first space special, why it suddenly closed, and their plans for Life World 2.0.

When Alex Bliss, Sarah Wilson, Peter Mills Weiss, Julia Mounsey, and Caroline Yost started a new underground arts space called Life World out of a soda canning factory in the fringe of industrial Gowanus, they didn’t have high hopes for the endeavor. It was the spring of 2021, near the end of the pandemic, a time when everything felt glaringly ephemeral. And even before the pandemic, they were used to seeing DIY spaces pop up in New York, only to quickly close down. “We thought, ‘let's do this for six months and see how it goes,’” recalls Bliss.

Though the space wasn’t immediately — or ever — profitable, it did quickly become the nexus of a community. The various founders came from different artistic backgrounds — film, theater, improv, stand-up — but shared an offbeat, anti-commercial sensibility. The space was a place where different forms converged, and different groups of artists influenced one another. On any given night, you might be one of five people in attendance for something only partially developed — but you also might witness magic.

And then, two years after Life World started, just as it was approaching sustainability, it all suddenly ended. By that point, the founders felt burnt out and weren’t itching to reopen Life World elsewhere. But fast-forward to this spring, and they did just that, in Bushwick. Here, Bliss and Wilson tell the story of how the first Life World came to be, why it closed, and what they wanted to do differently with a new space.

Origins: From garage to canning factory

Alex Bliss: I started renting out a garage in South Park Slope, where I used to live. It was the first time in my life that I had an office job and more than like $500 in my checking account. I didn't have any intention with it. I just always thought it would be cool to have a clubhouse. These guys were renovating a cute little storefront in my neighborhood, so I asked if it was available. This burly guy with a cigar said no, but then he walked me around the corner to a one-car garage and said, “Five hundred dollars a month.” And I was like, "OK." So I had that place for two or three years.

Sarah Wilson: He had a 16mm projector and started a Sunday screening series where he would get random films from the New York Public Library.

Bliss: I would try to get movies that were hard to find online.

Wilson: When I found out about Alex's space and that he did things like that I was like, "Woah, that's sick." I had lived in Philly where there are so many alternative spaces. And since moving to New York in 2018, there just didn't seem to be a lot besides Vital Joint and The Glove. And anyone who's got a little extra room, that is so valuable. I was doing standup comedy then, and I wanted to do an audience appreciation show that would be free and have a lot of fun giveaways for people in the audience. And I couldn't find a way to do it because you couldn't make shows free unless they were in a bar, and then at a bar you have to share the space with other bar activities. So I was kind of angling to do my show at his garage. We did a Halloween show, but then the pandemic happened. And what we thought was going to be the summer of our lives doing garage events ended abruptly.

Bliss: I did this little radio station thing during Covid, and that was fun but short-lived. I moved in with my dad in New Hampshire, then Sarah hit me up in 2021 when they were like, “Vaccine’s about to drop, y'all!”

Wilson: I thought I was making so much money because I had a freelance job making $300 a day. So I was like, “I'm rich.” And I wasn’t spending money during Covid since there was nothing to do. We wanted to do a slight elevation beyond what the garage had been. The garage didn't have a bathroom, or heating, or air conditioning, so we were like, “If we can just have those three things, that would be everything.” But we found out making that jump is a huge cost difference. We needed to get other people involved to be able to split the cost of the rent. So we asked Peter [Mills Weiss], Julia [Mounsey] and Caroline [Yost] to be part of it. I was the one looking for places on Craigslist. Again, it was really hard. Everything — especially centrally located — was more than $3,000 a month. And it's hard to find people who want shows done in their space. It makes way more sense for business owners to do almost anything else. So we learned that to run a space, you have to find a special person who is kind of down with the sickness. Or eccentric in some way. There’s a special kind of person out there who's down to do it with you. And in this case, it was this man who was running a soda canning operation, and he wanted to rent out a floor of a factory to artists. He gave us a great deal.

Bliss: We were sharing the floor with a band rehearsal studio, which is psychotic because the walls were paper thin. There was another guy who was like a crypto-hustler type who made fake Yu-Gi-Oh cards and 3D printed stick-and-poke kits. He would say things like, “Oh, I invented those fridge doors that are screens at 7/11” or whatever.

How the original space found its groove

Wilson: We were afraid no one would come, because it was in Gowanus, which is pretty far from where a lot of people live. In terms of programming, we had a vision that it would be for “special shows.” So we avoided monthly stand-up comedy shows, both because we didn't think they'd be well attended, being that far out, and also because if you have a bunch of monthly shows and they book the same hundred comedians, it's like you're just doing the same show twice a week every month. A lot of people would reach out to do a regular stand-up show, and then, when we would explain our “special show” policy, they would pitch their one-person show. And so it suddenly felt like, “Oh, we're a part of some kind of one-person show movement within the scene.” Really encouraging people to be like, “No, just do your hour. Do your half hour.”

Bliss: Also, we all have our own artistic disciplines. So at first, I think the curation was more or less just people we knew or knew tangentially who were doing cool stuff.

Wilson: I always have this problem with people wanting to say that Life World is a comedy space. I'm like, “No, you can do whatever you want here.” There's something reductive about that to me. But I'm going to keep talking about comedy, because that's kind of my world. I felt like before the pandemic happened, I knew I was part of the alternative comedy scene in New York, and felt very connected to those people. So I was like, “I'm in a community. If I open this space, I have a feeling they will come and fill it.” And then we had to bring in more of the other scenes.

Bliss: But also Peter and Julia like to make work with comedians like Tim Platt, Ike Ufomadu, River Ramirez, Brian Fiddyment. And I similarly make films with people from the alternative comedy world. So I feel like there is a through line.

Wilson: Comedy people are inherently DIY — the way that you put up your own shows that you produce, perform in, and write, and get audiences for. It's very much a showing-up-in-any-place-and-making-it-work sort of medium. We were excited to find people in other art forms who are down to work that way too. It also seemed like the place to show your film, either for the crew and cast, or premieres of micro-budget movies.

Bliss: I definitely saw a lot of stuff I wouldn't have otherwise seen. I did watch so many performers that I developed a sense of when someone has really figured out what their thing is. And maybe that inspired me to strive for that in my own work. I'm thinking of people like Brian Fiddyment, Blake Andrews, and Richard Perez. Many such cases.

Highlights

Wilson: I had a favorite thing I booked, which was SEM Ensemble. This person Peter Kotic, who I hadn't heard of, reached out. He’s like a 77-year-old composer-slash-conductor of contemporary classical music, and he wanted to do a six-hour nonstop performance. It was funny. I had to call him and get on the phone and be like, “Do you understand what the space is like? Why do you want to do it here?” And he was like, “We want to do it everywhere, in as many places as possible, so everyone can see it.” And then I had to get on the phone with him again when the advertising started, because he really didn't get why we didn't share the address publicly. But it worked out. It was cool to see someone doing that kind of music in the space. I like that kind of intergenerational connection, with people of all ages who are about the same artistic values and community values.

Bliss: We put on a show every night for the last week, before we shut down. Nick Naney did a weed-themed stand up show. And we were like, “Fuck it, it’s over,” and we let everybody smoke weed inside. There were only like fifteen people there passing around four joints during the show and everybody got really high and it was maybe the funniest show I've ever seen in my life. It was just like everyone was bombing, bombing, bombing, bombing. I was crying laughing all night. Nick does this thing called Schmiggy and I think we broke the world record for the most amount of Schmiggies that night. And he was so high that it was not clear if he understood how long the show was going, and it seemed like it might not end unless somebody intervened.

The end: How and why Life World suddenly closed

Wilson: The operation was barely held together, but a lot of things came together to make it work. There was a garage next door that was run by this sweet man named Carlos, and they would have parties out of their garage and dance on the sidewalk.

Bliss: We had a great vibe on the block. There was a biker gang, an auto body shop, and a deli on the corner. And everybody loved us. We lucked out. By the end, it was finally starting to feel like, “This is sustainable.”

And then we got shut down. Our neighbor had kids, and someone thought he was running an illegal daycare and reported the building. We never actually did anything wrong, but were asked to vacate because we were the most high-profile tenants. So that was a bummer. But by the time we stopped doing it, we were completely burnt out. We never got paid a dime. It was completely volunteer-run.

Wilson: But we had stopped losing money. Originally, we had been splitting the rent between us, and then we got to a point where we were breaking even, but nobody got paid.

Bliss: Whenever DIY spaces close, everyone's like, “New York is over.” So when we first started it, we thought, “let's do this for six months and see how it goes.” And then we did it for two years. By the time it shut down I felt like, “I don’t need to do this again.” It was a lot of work.

Trying again: Bigger, more legit, in Bushwick

Bliss: A few months after we closed, James Belfer reached out to us and said, “I'm interested in helping you guys do a second version of this.” He was like, “I could help you fund it a little bit, or find additional funding.” And that, to me, was like the prerequisite to doing it again. It would have to feel sustainable. People need to get compensated, even if it’s peanuts.

Wilson: We underwent a long process of figuring out how to legitimize, which involved speaking with lawyers and brokers. We had an architect working with us for a while. Right now we're an LLC that runs like a nonprofit. We have a fiscal sponsor, but want to be a nonprofit eventually. But it's really hard to run nonprofits. We just didn't want to do too much at once.

Bliss: We learned a lot about commercial real estate. I mean, you can actually negotiate on rent with commercial space, which is wild. It was interesting. We’re sort of small business owners now. I mean, we are. Which is such a funny situation to find ourselves in. I did not think when I was renting that garage that this is where it would lead. But it's kind of cool.

Wilson: It was telling that we ended up not finding it through the commercial market or working with a broker. We found it through our community and our relationships. Specifically, we found it through Theresa Buchester, who was the artistic director of the Brick, and before that ran Vital Joint, which was a DIY space. They knew Burke, who was running the space before. Burke built this awesome video studio and performance space, We Are Here, which he's been running for several years. He was finding it difficult to sustain, given the state of commercial filmmaking in the city not being what it used to be. He put so much time and love and energy into creating it, so he wanted to hand it off to people who would run it as an art space. And Theresa knew we were looking and put us in touch. We'd been looking at empty warehouse spaces that were like safety hazards and bombed out. It's disturbing. I mean, everybody knows that the real estate industry in New York City is fucked. But to actually see what is being offered and the prices it's going for…

Bliss: New York is always ending for somebody, but there are too many people for that ever really be true. I remember going to this punk show in Chinatown the week after the old space closed and thinking like, “You can't stop freaky young people from being freaks. And just because your community took a big L, doesn’t mean there aren’t other people out there.”

Wilson: The new space is like twice as big. Now we have a lighting grid that has like sixty lights in it. We really wanted it to be ADA compliant. The old place had stairs. And now we've got an elevator.

Bliss: We don’t want it to be as much of a party space as it was before. We're a little older. The world has changed a little bit. When we started the old space, the vaccine had just dropped. It was like, “Let's make out, do drugs, and party all night long.” Now it feels like maybe the world is ending, everybody's in their thirties, and… I don't know. So a big thing for me is transitioning into more of an arts institution over time, while still maintaining some of the original energy. It's not like we're selling out by any means. It’s the same shit. I’m not interested in growth, per say.

Wilson: There were people who were at the opening party who were concerned that it's going to be different now — that there were tons of people there, etc. And it was like, “No, we'll go back to programming things that are poorly attended. Don't worry.”

Bliss: Yeah, we got a couple of shows coming up. No one's gonna be there.

For upcoming shows at Life World, look here.

And here’s a story on another new Brooklyn film venue…

Jobs, programs, and other opportunities

The Listings

Jz Tinneny, a Brooklyn-based filmmaker, is looking for an experienced docu-fiction editor for a short film called CASINO. 2-3 week project. Strong assembly completed (audio synchronization/AE basics done). Logline: In this docu-fiction short, a group of retired community theater actors create a casino through a sense-memory workshop and explore the capacities of the workshop’s effect on their own histories, imaginations, and performances. Contact: casualtheory.xyz@gmail.com.

Ryan Martin Brown is looking for extras for a scene in LA on July 24. Fill out this form.

Jacob Mallin is currently looking for a 3D animator to create a few shots of planets nearly colliding for a short film he’s in post production on titled Last Night Alive. Paid. If interested, please reach out to jacobmallin2@gmail.com.

HKD Productions is raising finishing funds for The Audit, a dark comedy short about what your job is doing to your soul, starring Devon Werkheiser from Ned's Declassified School Survival Guide. Find out more here.

The Gotham is seeking an Expo & Public Programs Coordinator to support the organization’s upcoming Gotham Week Project Market and Expo. The Gotham Week Project Market, a flagship and legacy program of The Gotham, facilitates career-spanning relationships between emerging and established artists and distributors, financiers, production companies, festival programmers, sales and talent agents, and collaborators to provide creative and business opportunities to groundbreaking storytellers. More here.

No Film School recently published a massive list of summer film grants, labs, and fellowships. Check it out here.

If you would like to list in a future issue, either A) post in the Nothing Bogus chat thread, or B) email nothingbogus1@gmail.com with the subject “Listing.” (It’s FREE!) Include your email and all relevant details (price, dates, etc.).