From Storyboards to Screen: 'Gold and Mud'

Director Conor Dooley and Producer Lexi Tannenholtz on the joys and difficulties of making a movie where every scene is a single shot.

Hello! Welcome to Nothing Bogus, an Indie Film Listings+ newsletter. The + is commentary, interviews, dispatches, tutorials, and other groovy stuff. I’m going to start with the +. If you subscribed for the listings and only the listings, scroll as fast as you can to the bottom of this email. If you came for the +, no scrolling necessary :)

A few years ago, Conor Dooley was falling asleep when a short bit of dialogue popped into his head: "Any allergies to medicine?" "Just peanuts." "Peanuts aren't medicine." He chuckled and wrote down the exchange. When he read it back in the morning, he was still amused. But he didn’t know what — if anything — it might amount to. This wasn’t a concept or a character, and it didn’t contain much of a conflict. The lines lingered in his mind, though, and eventually he considered that maybe he could take a bunch of small moments like the one he’d jotted down and cobble them into a bigger story. “That became a challenge: What if I just put together a bunch of short little blips?” he says.

Many of the blips were mundane in isolation, but together they quickly amounted to something sweeping and existential: The story of a woman’s life, compressed into 21 shots, for a total runtime of nine minutes. Where we spend our whole lives gazing at other people’s faces, Dooley wanted to invert our normal mode of perception, and focus his camera solely on the face of this one woman (played wonderfully by Ana Fabrega). When I saw the short — Gold and Mud — at a live screening at the end of 2022, I was taken with the precision and specificity of Dooley’s vision (each frame is gorgeously constructed), but also how these little moments of humdrum absurdity (“I’m going on the cross-country rollercoaster trip without you, you bitch!”) amounted to a genuinely moving reflection on life and death and love. So, I was eager to speak to Dooley and producer1 Lexi Tannenholtz about how they pulled it off, both creatively and logistically.

When you were writing, did you have in mind the cinematic language you ended up using where each scene is one static shot and Ana Fabrega’s face is the only one you see?

Conor: Yeah, even in the script when someone has lines, they're described as like, "Hat" or "Balloon Arm." I knew exactly what part I wanted to show of these other people. That's what made it exciting to me. Each shot was just a decision of how close we are to Ana's face and how many details of her reacting to the world around her we get to see. Because it was just an inversion to me of our own singular outlook to our lives. We see it from our own eyeballs at our set height and that's our understanding of the world. So it was turning that around to look back into the eyes as they reflect all the good and bad.

Were some of the other bits things you accumulated over years, or did you write them all at the same time?

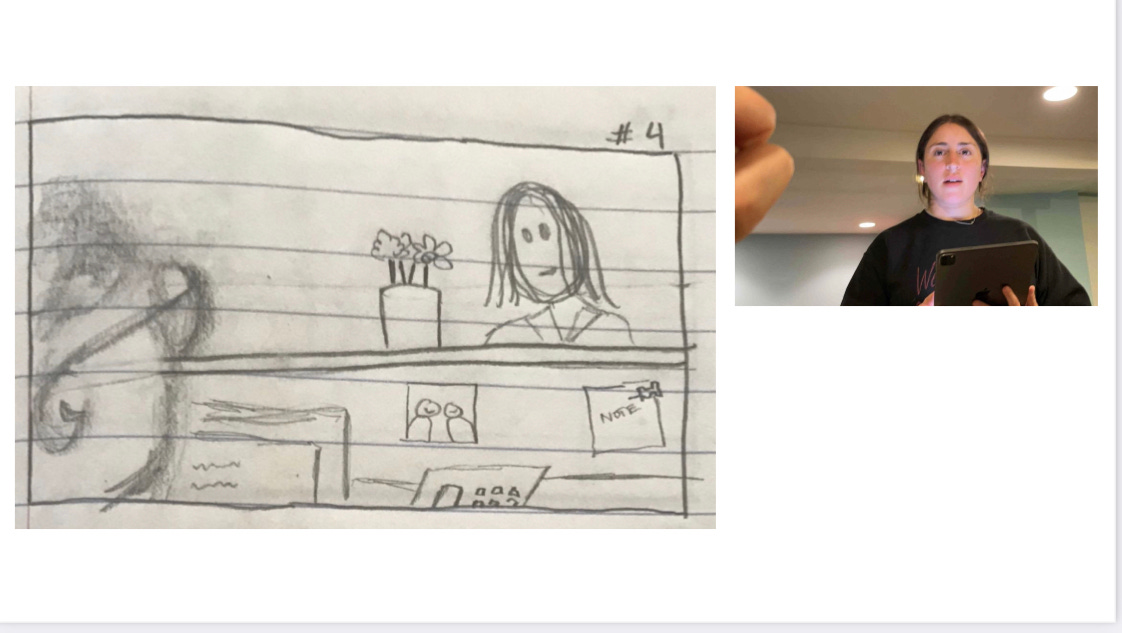

Conor: After the first one, I wrote it over a long weekend. And it just kind of flowed out with very little rewriting. And if you look at the script and then the storyboards versus the final film, it's very close. We just cut one scene that we shot. It was a scene of Ana coming home to her first wife. Her first wife is smoking just off camera, and Ana comes in and turns on the light and gets startled by her wife and drops a grocery bag and the whole scene is just her bobbing up and down behind a couch picking up all these smashed eggs while her wife doesn't really give a shit. For some reason the shot just didn't feel right. I think it was actually the first shot we did. So maybe we just hadn't hit our rhythm yet.

Did you have to adapt at all to the locations you were getting or the actors who were in it?

Conor: The whole thing was cast as I wrote it. The first page of the script was ideal cast, and it listed everyone who wound up being in it and doing the various voices and body parts. The actual locations came down to a production reality, but also to [our production designer] Becca Brooks Morrin being a genius and figuring out how to best utilize my house in Gowanus. We'd been planning on doing like three scenes there, and she was like, "I think we can do the whole thing here."

Lexi: I mean, Becca turned a canoe into a coffin! About two thirds of it was in Conor's house. But we also shot in an enormous church. We shot at a horse ranch. We shot at the beach. Conor and our DP Zac went to shoot one day on the Coney Island Cyclone. Even the animation that Graham Mason did at the end was a real shot that they got at Greenwood Cemetery, and then Graham animated over it. So everything was very precise.

Other than Ana, you're not seeing any of these actor's faces. So how did you think about casting? And how did you go about directing the actors?

Conor: The casting just came down to these being people I've worked with before, who I like and admire. So there was no one I was reaching out to who was a stranger. A lot of the scenes it was not the performer live on set. It was me or [producer] Sarah Wilson or Becca or Lexi acting as that slice of a body part. A lot of them came to the recording studio afterwards and it was just directing that performance in a sound booth. Or in Jo Firestone's case, she's on her iPhone in a closet and we're on a call together while she tries different country accents. It was kind of hard to do improvisation. But we'd usually get a take as scripted and then do one or two where they could do what they wanted. And those are some of my favorite moments. Like Ana's prolonged blathering at the horse ranch.

It seemed like you moved from set-up to set-up pretty seamlessly. Was there something you learned and would take into a next project?

Lexi: Everyone should make movies with only one angle! [laughs.] To set up and only have one angle and then move on, it's wild. And it wasn't a COVID decision or a money decision, either. It was just Conor's vision from the beginning to the end. One shot, close up, there's only body parts. But these parameters allowed us to get really creative. And we shot on film, so it had to be really precise for that reason too. I think that process was an exciting way to plan what we were doing.

Conor: As a discipline, knowing you have a finite amount of very expensive film, and you can allow yourself like a six-to-one shot ratio is one of the main reasons I love working with film. It's a nightmare to me to think about endlessly being able to do more takes on whatever digital medium. It was kind of a slow is smooth, smooth is fast set environment, where we were working constantly but it was never a rushed or stressful environment.

One of the things I like about the short is how it hits on all these big life moments but each of them is full of so much minutiae. Is that reflective of your life experience and outlook?

Conor: If anything reflects my experience in life it's the mix of high and low and absurd and real. So I think if there's any bit of my perspective being dipped into that kind of formula, it's just that you can go from belly-laughing to weeping pretty quickly. And when you look back it can feel like a lot of blips as your brain dumps the moments in between those things that it feels worthy of storing in your brain long-term.

But I also like the spanning of time in a short for the seasonality. In [my 2017 short] Observatory Blues we decided to shoot over a weekend in fall, winter, and spring, because it was just a way to build in seeming production value for no cost. So that it looked like, Oh, it was hot in that scene and it's snowy now, there's real intentionality there, this shoot went on for a while. It's a free way to make it feel bigger. Because if you're in one location and not much changes you can see how the movie was shot on a Saturday in somebody's apartment. But if you add changes of weather and season, it's going to feel much bigger. I think that's a way to break out of the confines of a short and make it feel like something grander and deeper.

Where did the monologue on the death bed come from?

Conor: It just fell out of my brain. I wanted it to feel like the brakes were slammed on. Because it was all so fast and you have exchanges that aren’t exactly groundbreaking writing, like: "What are you doing?" "What?" "What are you doing?" "Nothing." So I wanted to really shift the literary tone of what was being said and the pace at which it was being presented and just make it a rumination on memory and life and love and death.

Lexi: The thing I can't remember right now is how we wound up with the song, "Auld Lang Syne."

Conor: Well it's a marker of time. It's ringing in the new year, saying goodbye to the old year. So I thought it would be nice to use it as a marker for those spaces where we leap between ages. And also when it plays in It's a Wonderful Life, it still gives me chills. Some would call the film saccharine, but I love It's a Wonderful Life and I love the song at the end. So to me, it's a sweet song, it's a sad song, it's a marker of time. And that particular recording I found felt so textured and cool. That was one thing that wasn't in the script. That, and we added black interstitials. I'm personally a fan of the intermission to give people a second to let their brains catch up and prepare for what's next. It's potentially jarring to jump between ages without any acknowledgement. It helps you block it out.

Lexi, you've been working on a lot of different projects lately, including several features. I'm curious, from your perspective, what's the temperature like in the indie world right now? What's new? What's exciting? What's not?

Lexi: I appreciate you thinking I would possibly have an answer! [laughs.] I would say "the industry" seems to be obsessed with the word "genre" and at times allergic to the word "drama." And as a filmmaker who loves loves loves comedy "the industry" doesn't seem to hate this word right now, so I've personally never been more excited! I think in general people often say, "It's never been harder to make a film than it is today," but I do believe that's how the independent world always operates. It's always been hard and if it was easy, at least to me, it wouldn't be as fun and I don't think I would be doing it.

Listings

Tynan DeLong is looking for a Sony FS7 camera — built-out preferred. Email tynandelong@gmail.com.

From Emily Korteweg: Watch This Ready, the production company I help run, has built a new space in NY called Mulberry Studios as our HQ. It includes brand new post-production capabilities, two edit bays, a podcast/ADR studio, a screening room with a very large sofa, private offices, and common areas. After spending many hours in the edit, we wanted a different design and overall experience for ourselves, our friends, and our partners. All the spaces (which you can view here) except for our personal offices are open to rent. Email emily@watchthisready.com.

If you want to promote a screening of your film, I created a chat thread here.

And for those attending Sundance or Slamdance who want to link up, I created a chat thread here.

If you would like to list in a future issue, either A) post in the Nothing Bogus chat thread, or B) email nothingbogus1@gmail.com with the subject “Listing.” (It’s FREE!) Include your email and all relevant details (price, dates, etc.).

Tannenholtz co-produced the film with Sarah Wilson.