Vera Drew's Voice as an Editor

Drew talks editing for alt comedy, whether editors are becoming more valued, and how editing informed her writing and directing of 'The People’s Joker.'

Hello! Welcome to Nothing Bogus, an Indie Film Listings+ newsletter. The + is commentary, interviews, dispatches, tutorials, and other groovy stuff. I’m going to start with the +. If you subscribed for the listings and only the listings, scroll as fast as you can to the bottom of this email. If you came for the +, no scrolling necessary :)

Recently, I became interested in whether you could trace an editor’s voice across their filmography. Obviously, all editors are working in service of a given director’s vision. But most editors are hired for more than their fluency in Premier. Could a discerning viewer locate their contributions the way they might a favorite cinematographer? I spoke to a bunch of great editors — and some directors and producers, too — and wrote a long article on the subject for Filmmaker Magazine’s most recent issue. While I didn’t come to a firm answer, I did come away with a new appreciation for just how vital editors are to the filmmaking process.

One of my favorite conversations I had on the subject was with Vera Drew, who before directing this year’s delightfully incendiary The People’s Joker, had served as an editor for classic alt comedy shows like Comedy Bang! Bang!, Beef House, and I Think You Should Leave. Of all the editors I spoke to, Drew’s contributions were probably the most visible. Though these shows tended to star straight guys, Drew felt she was sometimes able to “bring an earnestness and a sincere queer vulnerability” in the edits. In my extended conversation with Drew, we talk about her experience editing for alt comedy, why editors are becoming more valued, and how editing was at the core of her writing and directing process for The People’s Joker.

Do you have general thoughts about whether — and how — an editor's sensibility ends up showing up in their work?

I think a lot of us from the Tim and Eric crowd kind of get lumped together, because we're all working with similar tools and approaches and stuff. But I definitely notice a difference in nuance and voice between a lot of those editors. Specifically when it comes to someone like Vic Berger, I could never do what he does, even though we kind of come from a similar world. I'm not too sure how I could best describe what my predilections and voice are. But I definitely notice it amongst my peers. I think some of us are hitting different access points even when we're working on some of the same shows sometimes.

When you say you could never do what Vic Berger does, what does that mean?

I remember when I first started seeing Vic's videos, it was all his remix stuff. I think the first thing I saw was his Katy Perry Pranking People remix thing. I can't quite put my finger on what makes Vic's videos his videos because there's such a specific voice to them. A lot of the political re-edits and stuff that he's done, I think he finds a real body horror aspect to videos I wouldn't necessarily see there. Especially as he was doing his Trump stuff, where Trump's face is becoming different colors and stuff. I think his approach to found footage and the remix style, only he could do that. And I say that as someone who's done a fair amount of video remix editing. Vic's playing with his own kind of dark magic when it comes to that kind of stuff.

Do you think that comes down to his reference points and the way his brain works, or is it also partially different practical skills?

I think it's a combination of both. When I first met Vic, I was asking him how he did a lot of that stuff, and it seemed like it was coming from a very intuitive place, which is I think how a lot of us work even though we're in a very technical space. It's really coming from instinct. I think of someone like Eric Notarnicola, who directed a lot of On Cinema and stuff like that. He's the most technically proficient editor I know. He can pick up any program in a way so many of us can't. But he's really approaching it from this gut place. And I think that's why editing is kind of an offshoot of directing and writing in a way. You can't really just write it all off as a technical field when so much of it is coming down to instinct and what's feeling right in a given moment.

I just was at a screening of this movie called All the Golden at WHAMMY!. It's by this filmmaker named Nate Wilson. You should see the movie. In terms of the potential editing and digital filmmaking has in terms of layers of story and all that stuff, it's completely unmatched with anything I've seen in years. I would literally put it up there with early Tim and Eric stuff when I saw it. Anybody who's working in a digital space, with editing or filmmaking or whatever, you're sitting at a computer and not developing film; you're not doing the hands-on technical aspects. And Nate described it in a way that's really interesting and I hadn't thought about, which is that that chemical process that happened with film is still happening when you're working in something like Premier. It's kind of just happening in our brain. I thought that was a perfect illustration for the kind of weird, loose, gut-level creating that comes with the kind of editing I like to do.

In this alt-comedy space, there are kind of built-in frameworks to the shows. So it's cool that you're still able to have different editors' voices come through in different episodes.

Yeah. I understand why AI is a threat to the way we understand movies and TV, but the human element is such a necessary part of filmmaking. And I feel like we're just hitting that when it comes to how these digital tools are used. I think specifically in animation and post production spaces, we're finally kind of in a space where the gig economy when it comes to editing is almost gone. And that's just because something happened within the last twenty years when a lot of the editing programs got a lot more user friendly. A lot of things are just edited now by story producers or creative lead showrunner positions and stuff. That's scary from a job perspective, because there's a lot less work out there. But I feel a lot more valued when I'm taking on an editing job now because I think there's an understanding of the importance of that human element. You need that editorial voice. I say this as someone who edited my own film, so I'm sort of breaking my own rule, but I really do think the success of an editor comes down to their removal from a project.

When I was working on Comedy Bang Bang! we were very close to set for all of it. It was very much a little lot where all the departments were very close together, but post production was still pretty removed from the process. We weren't there in the writers rooms. I would really only go to set if there was a celebrity I wanted to see. When we'd get all of our footage, we'd read the scripts or whatever. But it was this opportunity where it's like, "Here's some fresh eyes to look at this and bring it together." That show, and everything I got to do with Absolutely, was so fun because there was this implicit understanding that this is going to really come together in post. Our budgets are low and we're trying to do some ambitious stuff here, so we're going to have to figure out ways to make it work when these things don't look exactly how it looked on the page or in the director's head. I'm thankful to have come up in an environment like that. I think a ripple effect kind of happened in the last fifteen years or so where post production is taken a lot more seriously. Less just like the trolls in the back room who are going to polish your turd for you and more as actual artists and members of the team.

Do you have examples of times when you've felt valued as an editor?

Yes. I worked on this spinoff of The Eric Andre Show, which was KRFT Punk's Political Party. There wasn't a lot of lore to go off of, and in Dan Curry's script for the concept show there was a lot of wiggle room. There were a lot of places it could go. When I came in I got this hard drive full of footage that was amazing and hilarious, but it was kind of like, "How do we make a show out of this?" It was a lot of pranks and there was kind of a loose thread to follow. This was coming off of the experience of working with Sasha Baron Cohen on Who Is America?, and that was a show where Sasha does so much writing. There's a real science to how he does it. I was coming from an environment that was actually pretty restrictive in terms of how much of a writer I would get to be on a show, so I was pretty intimidated when I got all this footage. I was like, How do I thread the needle here? I talked to the director, Eric Notarnicola, and Dan, about it a little, and they were like, "We brought you in because you're an editor who thinks like a writer, so just do whatever you can." And more so than any editor's cut I've worked on in my life, I put so much of myself into that pilot.

It was at a time when we were all being told a lot that political comedy had to be a certain way. And coming from a place like working with Sasha where we were doing huge interviews with people like Dick Cheney, KRFT Punk was like, here's an opportunity to just play around in that space and have fun with it but be kind of edge-lordy and stupid. It became a thing where KRFT Punk's praying to the Abe Lincoln Memorial, so I'm going to composite my jaw onto Abraham Lincoln so Abe Lincoln can talk back.

And really it came down to the transitions we were doing between segments. I would go back and watch a lot of Monty Python stuff and a lot of mid seasons of Tim and Eric Awesome Show where they were doing a lot more graphically and digitally where they throw between segments, and I really leaned into that. Down to, it kind of looks like this guy is jacking off the Washington Memorial, so I'll take that, loop it, and we'll have the Washington Memorial cum and then we'll just go into this whole sequence of these sperm swimming to an egg and they'll all be presidential figures and they'll be singing "Yankee Doodle Dandy," and that's how we'll get there.

I'm doing this all kind of in a vacuum and kind of not knowing if this would land or if I'm just putting a lot of work into stuff [that will be cut].. But that was one where we screened my editor's cut and everyone was like, "Thank god we brought you in, because you just dug into this on a mentally ill level." And it was fun, because when it's a space where you're not being told there are rules you have to follow per se, it creates a certain freedom. But there are still lines to color inside because there's this language that's been established of what The Eric Andre Show's like, what political shows are like, and stuff. But within those lines, you have so much wiggle room to do so much crazy, weird shit.

So it seems like because you're able to move so much faster digitally, you're able to inject more of your own ideas, too. And there are also just more possibilities for what computers allow you to do.

Sometimes it can be overwhelming, because there's so much you can do in that digital space. Theoretically you can work on something forever. My movie's the perfect example of that. I could've been doing green screen removal on my movie for the rest of my life if I really wanted to. It can be a scary process. I think it's why a lot of people don't last long in that world. Because it kind of breaks your brain, having this unlimited range of creativity you can work within. But I wouldn't have it any other way. It's made me such a stronger artist. It's made me really have to know when something's done. And I think that's a value the best editors and artists I know have.

For a lot of these different shows where you weren't the director, it sounds like the directors were receptive to incorporating your vision in the edit.

Yeah. I've definitely encountered a few who were less receptive. I think one of my things is how I use music and sound is very specific to me. That hasn't always worked for everybody I've worked with. But especially someone like Tim Heidecker, you know exactly where you stand with him and if he finds something funny or not. It's always been really nice with him because he really just lets me do whatever the fuck I want. But with the caveat that if he doesn't like it, he tells me. And it's appreciated because I think the other trait of most editors is I think most of us do have a God complex and control issues. I think so many of us just are directors who happen to know how to use these programs, and this is how we're kind of getting there. But you've got to keep it in check. So much of the process for film and TV, it really only works if it is collaborative. So it's always a relief when a director or showrunner is meeting me on that level.

Famously, The People’s Joker came about because when Todd Phillips’s The Joker came out, Bri LeRose tweeted, “I will only watch this coward’s joker movie if Vera Drew re-edits it.” What do you think Bri imagined a Vera Drew edit to be?

I've been thinking about what that means for the last four years. I was in college when Awesome Show was coming out, and it really influenced me to a point where I would be a fool to pretend like I somehow developed my post production voice in a vacuum. The original teams of Awesome Show and the Tom Goes to the Mayor editors really informed my voice. So I think the Vera Drew edit style is very similar to the Tim and Eric fare. But I think, for lack of a better word, I'm just a lot gayer. There's a lot more color and — I don't want to say “sincerity” — but wearing the emotion on a sleeve, even if it means being cringe or embarrassing.

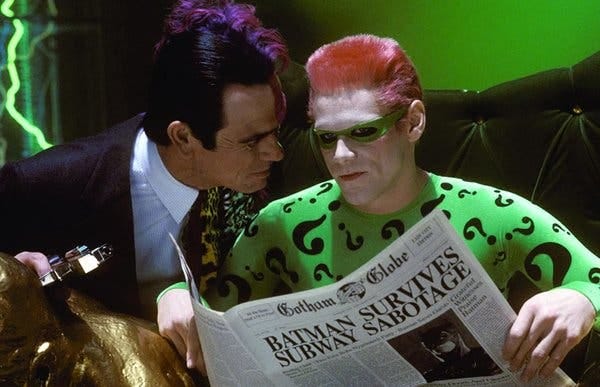

With something like Beefhouse, I was kind of the creative lead on that — third in command with Tim and Eric — and was really shaping that show at a script stage and with post production stuff. And that was a show that if anybody else had been in my position, it would have been completely different. I think I really bring an earnestness and a sincere queer vulnerability to these things that is kind of coming from my influences beyond alternative comedy. I'm really into Joel Schumacher, I'm really into Kenneth Anger, I'm really into soap operas and porn and exploitation films and stuff. You know, the only auteur in the world I think should be allowed to be called an auteur is Neel Breen. So many people describe his filmmaking as "failed seriousness" or whatever, but for me it's just so fucking beautiful. I really love art that is somebody leaning into their truest, most embarrassing voice, and I really do try to bring that into what I'm doing. So I think the Vera Drew edit of Todd Phillips' Joker was just always going to be a really colorful, really gay Batman movie with a lot of dick jokes and a lot of analog jokes and stuff like that.

With The People's Joker, it seems like you were writing the film through the editing in a way. But then as legal issues came up, you had to rewrite it that way even more.

That's kind of how it's been characterized. I do think, though, the movie started as a remix movie — a feature-length Everything Is Terrible sketch or something. It was me taking clips of the Todd Phillips Joker and swapping out backgrounds with stuff from Joel Schumacher Batman movies or '60s Batman. It didn't start as a narrative. I was just making a weird, experimental Joker thing. And it wasn't until I was really working on it that I was like, "You know, there's something else here. I want to make this like my memoir or something and talk about the last ten years of my life, and beyond. And put my experience with alternative comedy through a Gotham City lens." At that point, it was just a found footage movie. When I went back to Bri to write the script, we were still talking about it like we were taking clips from movies. We built a script that was structured around footage, concepts, and mythology that already existed.

So really, the process of writing and directing that movie felt a lot closer to editing the entire time because of that. It wasn't really until I got the team involved — and I had hundreds of artists working on it — that it became clear to me that maybe the move here is not to use any footage from preexisting things. And part of that was from a legal standpoint. When that decision was made, that was about a year or so into the project and it was kind of at this point where it's like, OK, I've invested a lot of time and energy into this and I want to be able to screen it for people, so why don't I really just lean in and recreate these things instead of using footage?

But because I had this found footage version of the movie assembled, when we got to set to shoot our live action components, I theoretically had the whole movie completely edited before we even shot it. I had an animatic of it that was assembled together using all these scenes and set pieces we were parodying. I only had five days to film it because of budgetary constraints, where I had like $20K to really film something of feature length. And I think we were only able to accomplish that — not only because of my editing experience, but just because for almost a year before we got to set I really built a feature length pre-viz of the entire movie.

I'm not sure if I'll ever have that luxury again. The stuff I'm developing right now, I'm making a point of telling everyone I work with that that was my approach. I think when you take that approach — even if you're just going to do it with storyboarding — you really are saving yourself and your team a lot of time once you get to set. You're having a baseline of what the rhythm of this movie is going to be and how it's going to flow together. And within that, too, there was a lot of room for me to be really rigid and be precious about the pacing and stuff. It was an impossible movie to make. There were 1600 VFX shots in that film. And it was really just me, a very tired, mentally ill stoner, who had wrangled a team of other people who are also that. So it was a lot of work, but because of that, and because of how long the process was, because I was really meeting it with that flexibility of figuring out what this is as we're making it, I think that's why it turned out so good. I think a lot of it comes down to having the editing experience I have and preparing the animatics and stuff, but I think so much of it is because I really met the film on that intuitive level that I was describing when it comes to just working in the edit bay.

Listings

Multitude Films and Brown Girls Doc Mafia are seeking proposals for four doc shorts that explore reparations beyond the financial models most often covered in mainstream media. Deadline Nov. 15. Application and more info here.

Antigravity Academy is taking applications for its second Screenwriter’s Camp. Applications open Oct. 21 through Nov. 22. Camp runs May 23 - 28, 2025. More here.

Josh Palmer is seeking a Gaffer for a micro-budget feature in Cape Cod, shooting Nov 10-25. Ideally owns equipment or can source lights. Seeking sensitivity, communication, and taste over technical ability. DP: Marcell Lobenwein. Paid, lodging + travel covered. contact: jeliaspalmer@gmail.com.

Casting call for a new feature film shooting Spring 2025 in NYC. Non-Union and must be able to work as a NYC local. Synopsis and project details on this document: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1hqKKWIRmHndfIMAwZqGZLfvsG58blVqDdwTPNO-1UAg/edit?usp=sharing, submit to: freakscenellc@gmail.com.

The same project is seeking production designer. Synopsis: A game developer enters into a love triangle with an older investment banker and a former college classmate. Paid, must be able to work as a NYC local. Email resume and work samples to freakscenellc@gmail.com.

June & Naya Get A Perm, a short coming-of-age film, is casting two leads (both paid): June (24, East Asian, effortlessly cool yet genuine) and Naya (12, Black, optimist in the face of insurmountable insecurity). Shoots in NJ Nov. 8, 9, 10, 15. Apply here.

Nepali Female Filmmakers is holding a free cinematography workshop for Nepali women filmmakers Nov. 10 - 16. Deadline to apply Oct 25. More here.

The great Paul Schrader is apparently in need of an assistant for a “shit and ice cream” kind of role. Email schraderproductions@gmail.com. Good luck!

Stephanie Ibarra recently launched a crowdfunding campaign for her upcoming film Todo el Tiempo en el Mundo, which is shooting in Chile this December! The campaign will be live until October 24th. Help fund the film here and follow the film on IG @todoeltiempofilm.

A film called Bet On It is casting two roles: Bella (24, F, a witty, exhausted romantic who dives headfirst into any challenge) and Kai (25, M, a charming yet cynical dater, who uses humor and detachment to makes his frustration with love). Email Yasemin Cobanoglu at yc5084@nyu.edu

No Film School recently published a massive list of fall film grants, labs, and fellowships. Check it out here.

Neighbors, a documentary series, is searching for unique ongoing neighbor/neighborhood disputes and interesting stories. Email HelloNeighborsTV@gmail.com.

If you would like to list in a future issue, either A) post in the Nothing Bogus chat thread, or B) email nothingbogus1@gmail.com with the subject “Listing.” (It’s FREE!) Include your email and all relevant details (price, dates, etc.).