With 'This Closeness,' Kit Zauhar Portrays Intimacy as a Battleground

We discuss the power of gossip, depicting incels, and the polarizing song the film goes out on.

Hello! Welcome to Nothing Bogus, an Indie Film Listings+ newsletter. The + is commentary, interviews, dispatches, tutorials, and other groovy stuff. I’m going to start with the +. If you subscribed for the listings and only the listings, scroll as fast as you can to the bottom of this email. If you came for the +, no scrolling necessary :)

When Kit Zauhar was just out of college, a boyfriend who was between apartments stayed at an AirBnB in Bushwick, with a host who, she says, “catfished him a little bit.” The host’s “profile picture was way younger than he actually was,” and he was socially awkward and noticeably lonely. The experience of staying with that host was “incredibly sad,” but it also piqued Zauhar’s interest. “Lonely people are very fascinating because they have this very rich interior world that they have to keep fortifying and relying on more and more as they get older and lonelier,” Zauhar says. “Even when they meet people, I think the interior world is kind of coming up to bat against this newfound intimacy and connection. So as somebody who's always stuck in my head, during the pandemic — which was so much about isolation and loneliness — I started thinking about him again.”

Around the same time, Zauhar was inspired by an n+1 story by Tony Tulathimutte called “The Feminist,” which ends up being the origin story for an incel. Where most depictions of incels felt like caricatures to Zauhar, Tulathimutte’s story was able to bring nuance to one of these people by depicting him at an early stage. “So that was something else I was thinking about while writing this: How to make something that could suggest an origin story of an incel.”

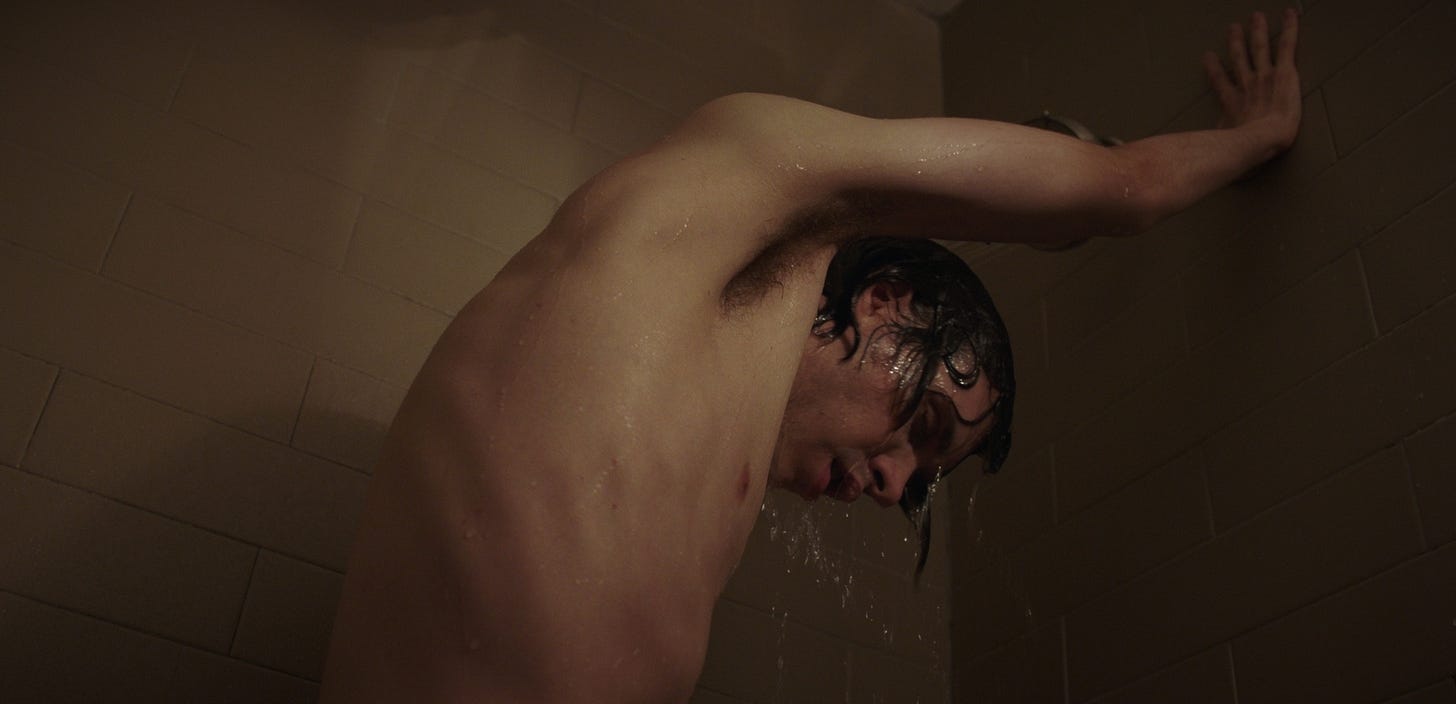

Initially, Zauhar conceived of the story — about a young couple that stays with an awkward AirBnB host during a trip to the boyfriend’s high school reunion — as a stage play. But as COVID hit, it became increasingly clear that there wasn’t going to be much live theater any time soon, and she reworked it as a screenplay. The success of Zauhar’s feature debut, 2021’s Actual People, helped her attain some modest resources — though she didn’t need much. The film, which she called This Closeness, only called for four actors and one location. It was released in New York this past weekend, and it’s easy to marvel at how taut and quietly tense it remains throughout. But in juxtaposing one couple’s fraught intimacy with a single man’s lack thereof, Zauhar also crafts an incredibly layered and honest depiction of the desire for connection, and its limitations.

Adam, played by Ian Edlund, is a lonely AirBnB host who seems like an incel-in-the-making. Tell me about you approached writing that character. Did it come naturally?

Zauhar: Yeah, maybe we all have a little incel in us. [Laughs.] I really just love listening to different people's conversations. That's something I've always been fascinated by. Walking down the street, if there's a fight going on I'll just stop and listen to it until it feels like it could be dangerous for me to stay. I just love hearing how people talk.

I think high school is also a theme of this film in a lot of ways. I went to a really big high school where there were a lot of really different kinds of disparate characters. And you did end up talking to some of these people in a way that in other high schools you were shielded from because of whatever social or academic boundaries. So I remember conversations I had with these lonely guys and ways I tried to level with them. I remember having some really nice conversations with them. It's kind of like they're open wounds, but they're really good at curling up so no one can see that.

That observational quality you're describing makes me think about the ASMR aspect of the movie. That's kind of what ASMR is all about, tuning into these very small details. So I'm wondering how that all fit into this story for you?

I've wanted to make a movie that incorporated ASMR since I discovered the phenomenon. I used to struggle with insomnia — I still do, not to the same degree — because I was, like, addicted to Ambien, etc. etc. So when I was weaning myself from Ambien, I started listening to ASMR a lot. This was around 2014, 2015. And it's kind of a hack to create mood, tone, atmosphere, intimacy. And it also obviously has this weird sexual undertone, especially as it's progressed. So it's this very weird thing that had so many weird layers and preconceived notions attached to it. So I always wanted to incorporate it. And I thought, Well, this is a film about uneasy intimacy. And intimacy used as a weapon or a tool. And obviously ASMR is a way of commodifying intimacy and monetizing it. So it was my way of exploring intimacy not just as this tender concept, but as this thing with more power and ways of being manipulated and [enacting] manipulation.

It also feels like Adam in a way is the natural audience for Tessa’s videos. But online they wouldn't actually be put in the same room. And when that actually happens it's an awkward dynamic.

I think what needs to be acknowledged is that we're a generation that's chronically online. But I just don't find internet movies that interesting. Writing is really amazing obviously, but I don't want to watch a movie where a character tries to write. So it's like these weird things that are compelling in real life but you see the air get sucked out of them when you try and film it. So for me, it was trying to find ways to convey that these aren't luddites. They're very much part of the culture and the current conversation and milieu. But not having them be constantly actually interacting with technology. And also, ASMR stuff is so weird looking. It's fun to show because it's so bizarre.

It makes perfect sense that this began as a theater piece because it all takes place in this one apartment. But the magic trick of the movie to me is that it remains compelling despite all being set in this one place. How did you think about the structure of it?

I think it's just keeping these three people surprising each other in some ways. Acting is all about surprising — not surprising the audience necessarily. The audience can see this whole thing that has its peaks and valleys. But as an actor, your goal is to surprise the other actor, so you do things that feel human and authentic and reactionary as opposed to rehearsed. So that's how to structure good character dynamics, to surprise each other.

And something I love is movies that feel like gossip — when you're constantly learning shit about other people that you're not supposed to know. I think it's also kind of a hack to stay interested. You're like, I'm not supposed to know this and now I do. And it kind of makes you a co-conspirator with the other characters and makes you have more of an emotional stake in it. I think also because these characters are people we know, there's an easy intimacy, and this emotional investment is sort of baked into it.

How did This Closeness change from its initial conception as a play to it becoming a movie?

I think the luxury of cinema is that you have the gift of composition. I think it was just really being careful about how we were composing shots, knowing they would have to have a longevity and sustain people's attention, and bring an aesthetic comfort or beauty while showcasing the acting.

What directions did you give your cinematographer, Kayla Hoff?

In the moment, I'm like, What the fuck do I say to a cinematographer? I don't know that much about cameras. I should know more. But what we did was create a mood board on Are.na. I love Are.na, I use it all the time. I check it more than Instagram. It's way more engaging and beautiful. We just started compiling images and film stills and also photography. When I start thinking about a movie I don’t necessarily like to study film stills, because film stills can look really beautiful, but then you watch the movie and you're like, They just chose the best film still from the entire movie and the rest of it doesn't look like this. But photography is something I really love studying and looking at — and paintings as well. So we were looking at some photographers when we were looking at light quality. So I think it is just trying to figure out what the language is between the two of you. What are the things you agree on?

Kayla Hoff, who was the DP, is really wonderful. And she has such a keen and unique eye. I watch so many DP reels and they just all look the same to me. But both of us did have this investment in composition, in a kind of photographical language. Also reveling in the possibilities of natural light. It was such a great apartment and it got such good light, too. It had those two skylights. And just understanding the real world is beautiful. That's why we want to film it. That was our intention when we started art. So we had very few lights. There were very few tricks we were doing. We were just like, How can we frame it well so the light shines nicely and the actors look good but also natural?

The hardest part of what you’re describing seems like it's that the world is very beautiful but minimalistic AirBnBs are not usually.

But I kind of love liminal spaces like that. I've always thought they were very interesting and beautiful. I've also just spent far too long inside them. So maybe that's kind of a coping mechanism. Beauty is everywhere. That's so corny and not necessarily true. But maybe that's also why you see that in the film, because I do genuinely feel like there were parts of the apartment and parts of how the light hit and what we were able to get that were very beautiful and painterly to me. I didn't go into the apartment going, "This place is a shithole. How are we going to make this work?" I was like, "Oh wow, I like this."

How did the movie then change in the edit?

We cut a lot of scenes. I'm an over-writer, so there were whole scenes we axed out. We also edited the whole thing in two or three weeks. Brian Kinnes, my editor, is kind of a beast. We truly went into the edit like Vikings or Huns or something. Going in and slashing whole structures apart and letting things fall to pieces.

The scene between my character, Jessie Pinnick's character, and Zane Pais's character was originally going to be a oner, much like the fight scene between Zane and I. So it was like a sustained twenty-two minute conversation — which we got! We spent a whole day just doing that. But in the edit everyone was like, "This is kind of pretentious. This is kind of too long." And I was like, "OK, maybe I am just kind of pretentious, I guess." But that was one of the darlings I had to kill. At the end of that [shooting] day, we'd been drinking fake beer and a little real beer at some points too, so we're a little woozy; we'd been doing this scene for like five hours straight. And everyone was like, "Get in and get closeups just to have them." So we ended up needing it. And we used those to cut through the scene and make it shorter. But nothing structurally changed.

Was there anything going into the movie that you wanted to do differently than on Actual People?

Yeah. I was like 23 or 24 when we shot Actual People. There were less things I learned and more things I was assured of or not assured of. On Actual People, I was also working with mostly my friends so there was an intimacy and camaraderie and lack of professionalism that was not present on This Closeness. On one of the last days of Actual People I turned to my friend Jackson, because we had one car that we were using and two of the tires blew out on the same side. So we're driving to the nearest service station and I was just like, "Should I just give up?" Which is so unprofessional, so not cool to say. He was like, "Kit, what are you talking about? Don't we have like one day left to shoot this movie?" And I think for me, as I've gone through the process more and more, your job as a director is also just to be the project's biggest cheerleader and to fake it ‘til you make it. It's really hard when you're tired and emotionally exhausted; you can let your worst instincts come out. But as I've gone through the process and gotten better and better at this, I will not let that happen. Because it really is no one else's problem. It's barely your problem, honestly. You have so much shit to do.

How many days did you shoot?

Thirteen, I think. And we were returning to the same place every day, so it really felt at some points like you're just doing a play.

There's this quiet tension coursing through the film. I'm curious about the ways you found that as a tone.

I think it's the baked intention because of circumstance — confined space, weird guy next door to you. I think people also have a lot of implicit assumptions — young woman, much bigger guy who knows where she is whenever she's home, he's kind of weird — that instantly conjure these horror movie expectations.

But I think the tension also comes from all these things being known that should not be known. I think whenever you hold a secret, whether it be your own or somebody else's, you feel a tension within yourself, because there's the moral obligations, there's the deliciousness of knowing something you shouldn't. There's also the responsibility of being privy to that and carrying it. These are all things that you're grappling with at once. This is just being done at a larger scale that's out of the audience's control, which I think makes the tension get stretched tauter and tauter as the movie continues.

There's this line Tessa says to her therapist in response to her therapist asking why it's so important to her to make the relationship work. She says, "Because it means I've won." That felt like a really important line in the movie. Where did it come from and what was the intention behind it?

I think it goes back to the theme of intimacy. A lot of times people see intimacy as this end-all-be-all. Like once it's there, it's this sort of plush, nullifying, tender landing for you where everything is cushy and syrupy and sentimental. And that's just not how I've ever seen intimacy. I think it can be kind of a battleground. Think about how much more bitterly and tactfully you can fight with someone you really really know. It can be a very harsh, disturbing thing to be intimate with someone. Even sex is kind of gross and weird if you think about it a little too long.

So for me, these are two people who are really drawn to each other because they see intimacy as a battleground. Through these concepts we'd associate with war: territory, belonging, winning and losing. So for her, if she gave up this relationship with Ben, it would be like she'd be losing in this maybe lifelong battle to gain some kind of hold over her idea of intimacy. When really, in the most therapizey way possible, the whole idea of winning intimacy is just giving into it and accepting it and nourishing it.

Tell me about the song at the end.

It's a Department of Eagles cover of a JoJo song. It just came up on my Spotify one day randomly, and I was just like, "Wait, this song is kind of awesome." It's so weird. The lyrics themselves hit upon a lot of the themes in the movie. And I'm also just kind of an indie music head, I guess. I unfortunately am probably going to be one of those old people whose music taste just does not evolve anymore. But I really love Grizzly Bear and Department of Eagles. And I felt like the song was kind of haunting and ethereal, but it's cut by this comedic value of being a cover of a teen pop song. And that felt very high school reunion to me, too. I kind of imagined a high school reunion where everyone is dead and dancing in a purgatory to this song. Some of my friends have been like, "That is such a wild song choice," and some really like it.

Listings

From Bucky Illingworth: Have an affordable / sliding scale Super 16mm package available in NYC. It's an Arri SR2, PL Mount, HD tap, 2 mags Otar Illumina Lenses (9.5, 12, 16, 25). Insurance is required for rentals but also open to work as a DP / operator. Just looking to make shooting on film more accessible for people! Email: email@bucky.website.

The short thesis film, Safe In My Skin, is casting right now. It is shooting Upstate New York in late August and early October. This is a paid opportunity and it is open to actors and non-actors. If interested email casting director Manuela at safeinmyskin2024@gmail.com with a photo of you and any links to your previous work! Looking for:

Male Talent / Chinese-American (18 - 25 yrs old) *Must speak Mandarin *Ideally knows how to ride a skateboard

Male Talent / Caucasian (18-25 yrs old)

Female Talent / Caucasian (18-25 yrs old)

Anna Torzullo and Steph Ibarra are hosting a film screening of a collection of shorts at Kaleidoscope on June 21st, to raise money for the production of a short film shooting in Chile this winter. RSVP at this eventbrite (tickets are $17 at the door).

Edward Frumkin is looking for programming, copywriting (like press kits), and administrative/production assistant opportunities. He's an experienced writer who's written for places such as BOMB, IndieWire, The Daily Beast, and The Film Stage, screened for Camden and True/False Film Festivals, and programmed for 2024 Big Sky Documentary Film Festival. He was also a driving PA on PJ Raval's upcoming nonfiction project In Plain Sight. He can be reached at edfrumact@gmail.com.

Nothing Bogus is looking for summer interns. Interns would help with collecting listings, operating social media accounts, and they would have the opportunity to interview filmmakers (or other interesting people within the indie film universe). Good for college students with interest in film and/or journalism. Email nothingbogus1@gmail.com if interested.

Also, the newsletter finally has an Instagram account. Follow it here.

If you would like to list in a future issue, either A) post in the Nothing Bogus chat thread, or B) email nothingbogus1@gmail.com with the subject “Listing.” (It’s FREE!) Include your email and all relevant details (price, dates, etc.).