Why Line Producing Is as Much a People Job as a Numbers Job

Pete McClellan shares budgeting tips and makes the case that your little indie's breakeven point should probably be higher.

Hello! Welcome to Nothing Bogus, an Indie Film Listings+ newsletter. The + is commentary, interviews, dispatches, tutorials, and other groovy stuff. I’m going to start with the +. If you subscribed for the listings and only the listings, scroll as fast as you can to the bottom of this email. If you came for the +, no scrolling necessary :)

A line producer’s job revolves around creating and overseeing a film’s budget. But Pete McClellan, who has line produced for films like Lingua Franca and All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt, views the job more as “people management than budget management.” There is the adding and subtracting of expenses, sure, but the crux of the job comes in building trust, communicating clearly, and managing expectations. As he’s gotten more experience, McClellan has learned when to approve expenses that are beyond the scope of an original budget; how to artfully move money around so that the production stays under budget; and how to maintain “healthy relationships with department heads to create an environment of us all being on the same team.”

In addition to his line producing work, this past week, McClellan’s first feature as a capital-P producer was released: Nicole Riegel’s Dandelion. So in addition to the ins-and-outs of budgeting, we discussed the relationship-building necessary for producing, and some longstanding gripes McClellan has had with the Esquire article I wrote last year about the wave of cool microbudget movies sprouting up.

Let’s talk about smaller indies. Last year, when I wrote about the wave of cool micro budget movies coming out, there were some things you pushed back against.

Something that stuck out to me in the article was Ryan [Martin Brown]'s quote about how all of a sudden if you start selling to these big production companies this idea of being able to make things for smaller and smaller budgets, that's scary because these small budgets are not sustainable. So an idea I'm trying to push is that if your small indie movie is going to have success it's most likely going to have big success. There are very few things that end up in this weird in-between of making a few hundred thousand dollars or making a million dollars. It's either going to make close to nothing, or you're if you’re lucky and it does have commercial appeal you’re going to get back a couple million bucks.

So this idea that there's this magic number of how big our budget should be going in is misguided. It needs to be "This is how much it costs to make a movie" as opposed to "We're willing to make sacrifices because we believe in this." The people paying for the product need to know that the cost has gone up. Which is why nothing is being made right now, because the cost has gone up and people are trying to figure out how to work around that. But it's like, "Oh, we're going to skimp back. The investors wanted to give us a million dollars to make the movie, but we feel like we might not make a million dollars, maybe we'll make $250K back, so we'll make the movie for $250K." Well it's like, "You all lose outright, and then even if the movie does have success they're probably going to make over a million dollars." There's such a small target on the dartboard that is "OK, we made back three hundred thousand dollars." As someone who makes a living making movies, I don't want to see us collapse into the only people who make movies are the people who can afford to not get paid on them. That's such a scary world. So I want to advocate that movies are super expensive, and they should be because you're paying a lot of people to do a thing.

Is what you're saying that the thirty thousand dollar movie should be three hundred thousand dollars?

No, kind of the other way around. It's going to sound like a cheapskate position, but I highly advocate that you don't pay your friends on a short film because I think the amount of money you can offer them is so low and the reason they're doing it is not to get a paycheck, it's to help you out. And if it's not a friend, you have to hire the person for sure. But when you're starting out and proving yourself as a director, go make something for super cheap. Like, zero dollars. Prove that you can direct and come up with story ideas.

So on those slightly bigger small indies, your breakeven point should be higher in a lot of cases. And you shouldn't be making the movie for such a small number where you're now exploiting people.

Or you don't even have the money to make the thing you're trying to make. That's another thing. You're like, "I'm going to bring my costs so low that I have a good chance to make my money back." But then your movie turns out shit. Great, you saved $200K on your $800K movie when you could've spent the proper amount and given yourself a chance to make your money back.

Getting more into the weeds of budgets, most of your work has been as a line producer. Are there places you think people tend to skimp and not spend enough?

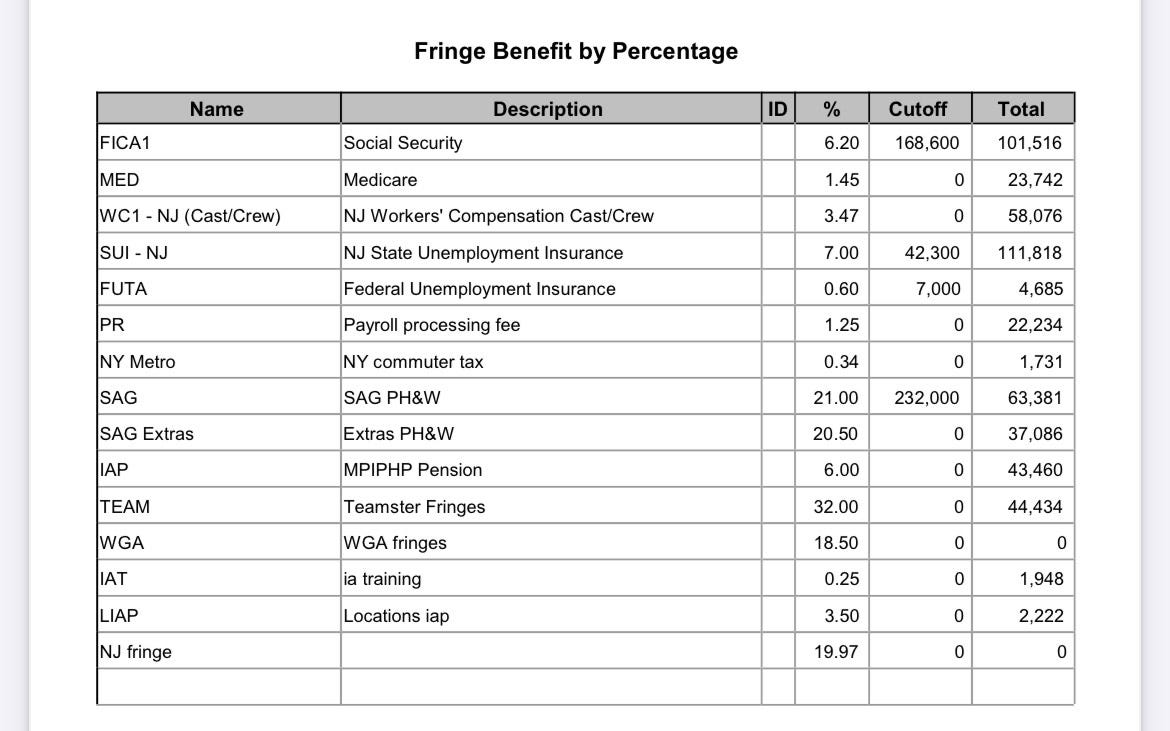

It's rare to find a budget from someone who knows what they're doing where I'm like, "Oh god, what are we doing here?" But people breaking into line producing, you've got to understand fringes. That's your taxes, your union dues, all the costs of doing business. Often, especially when you're talking sub-$1 million and you're trying to skimp on every cost, it's like, "Do you know what worker's comp is? You've got to have worker's comp, because if someone burns their hand on your set they're going to sue you if they can't go to the doctor."

And this is the fine line between a career and a hobby. What we're talking about here is career filmmaking. When folks from the hobbyist world are trying to break into that, they forget taxes owed on labor. I think people try to skimp on crew size, and I think you've got to be a really specific type of film to be able to do that. You're not setting yourself up for success if you have one person doing hair and makeup and wardrobe. Look to a union set, look at how many people they have. Of course you're going to slim it back. But people try to eliminate whole departments like, "Oh, we'll have our art director also do props." It's like, "There is a reason those are separate departments.” And it's just knowing your own script to know what you can get away with.

I think about how in baseball, teams started doing a shift on defense. They have the same number of players on the field, but all of a sudden you're not putting a shortstop in the shortstop position. And it works for them. I'm wondering if there are analogous ways film sets could be more efficient than whatever the orthodoxy is.

I've been kicking that around too with a project I got recently attached to. We're applying for a grant and the grant is for 200,000 euros. In the application form, building the budget, I'm like, "Good god, how do I do this?" And it requires you to kind of rethink how you make a movie. If we're going to do this, it's like with a crew of five people. And yeah, that doesn't include a wardrobe specific person. But it's so material specific. And as you get more experience as a producer, you make those decisions correctly. Versus when you're starting you're still making those decisions, but you're making mistakes. And that's OK, you can learn from that.

I think a savvy production has the line producer in a creative conversation with the director, making sure that you are on the same page in terms of their priorities. Yes, some departments will bloat. But as long as that bloat is happening in the same organic direction as the director's priorities, then I think it's OK. Where I think you get yourself in trouble is twofold: One, you don't see eye to eye with the director, either because you're a bad line producer or they're not bringing you in. Or, it's the line producer trying to make their life easy and not think about the project first and foremost.

Here's a big way I screwed up line producing on my first job: SAG contracts are eight hours, not a twelve hour day. And so many times I'll get a budget and they've plugged in the SAG scale and it's for eight hours. I go the other way, and I assume they're going to get an hour of OT so you can calculate into your budget what an actor's going to get paid and estimate ideally more than they're actually going to get. And that's protection for you in case your AD calls up and says they need an hour. Also it's a good way to store money that no one's ever going to balk at.

Are there other pieces of advice you give to first time line producers?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Nothing Bogus to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.