What 'Goodfellas' Shares with 'Silence of the Lambs': Kristi Zea

The insanely accomplished production designer talks craft, recounts some wild stories, and gets real about the job's demands.

Hello! Welcome to Nothing Bogus, an Indie Film Listings+ newsletter. The + is commentary, interviews, dispatches, tutorials, and other groovy stuff. I’m going to start with the +. If you subscribed for the listings and only the listings, scroll as fast as you can to the bottom of this email. If you came for the +, no scrolling necessary :)

by Charles Caster-Dudzick

Just peek at her IMDB and out hop names like Scorcese, Demme, Mendes, Meyers, Stone, Deavere Smith, and Murphy. Over the last 40+ years, Kristi Zea has been an Art Department Champion. She started in styling and costumes, before moving on to production design, and then producing and directing. Across all of these roles, and with many different collaborators, she has brought a unique eye and insane work ethic.

Which is why, in 2016, when she needed a driver-PA, I jumped at the opportunity. Chauffeuring her from art department offices, to studio sets, locations, workshops, tech scouts, props/fabrication houses, and material suppliers, or wherever this remarkably busy job demanded her to go, proved to be the greatest crash course in Art Department work a guy could ask for. Better yet, we became good friends, and then collaborators — editing, scoring, and co-producing Talking Pictures, a short kinetic poetry-romp follow-up to her 2016 documentary of artist Elizabeth Murray.

Recently, we caught up to talk about her career trajectory, experiences across the decades in various art departments, and the boons, risks, and costs of a long life in the film industry.

Charles Caster-Dudzick: How did costumes and fashion prepare you for film production?

Kristi Zea: It taught me everything about pressure, about having to find the right stuff, about dealing with clients. It gave me a tremendous amount of strength and conviction and energy. I was running around the city all day long going in and out of stores, buying or designing special clothing. If I needed a certain kind of suit made, I had enough experience from my days sewing my own clothing… it was a madhouse, it was crazy. I was looking for locations and booking talent, all the props, all the actors, so my job was huge.

What circumstances brought you into film?

I had a friend, Pam Adler, who was hired as the assistant to Alan Marshall, who is a British producer who was coming into town with Alan Parker to shoot Fame. And that was a big, big production in those days. Thirteen million dollars was a lot of money in 1979. I told Pam that I wanted to interview for the job of costume designer. So I met Alan Parker. He had come out of the commercial world, he knew Norm Griner at Horn/Griner and all the people that I'd been styling for. I went into his office and I said I'd like to do this film. I had gone to Music and Art High School, and Fame was about the High School of Performing Arts. Not only did I understand the world because I had gone there, I also knew about costumes, I'd been styling all this time, I knew what was cool and what wasn't. He hired me and he said, “Just don't fuck up!” That was my first job in the film business.

From that point on, I just started doing more and more films as a costume designer: Terms of Endearment, Silverado, this crazy film called Tattoo. I got a call from David Seltzer, who was a film director, and he said, “I'm doing a film in Chicago and it's called Lucas and it would be perfect for you because it's all about high school students and I'd love you to do it.” I don't know what caused me to say anything like this, but I said, “Who's designing the show?” He said “Well, we haven't picked anyone yet.” And I said, “Well, I'd like to production design the show. Because I've done Fame already, I don't want to [costume design] another high school movie. But I'd like to production design it.” He called me back later and said James L. Brooks says, “Whatever she wants to do, just get her.” So that's how I started in production design. I did Lucas and a few other films after that.

Then after a little bit of time, I got a call from Kenny Utt, who was a major producer in New York City and he said, “Jonathan Demme is looking for a new pair of eyes for his movie Married to the Mob and we'd like you to come in and meet him.” I read the script and then I thought Hmm I know this world. I went to a photographic bookstore and pulled out a few seminal books about suburbia. There was this crazy book by Diane Arbus’s daughter Amy… portraits of how people live and what their offices or their homes look like. I brought those two books to them and said, “I think this is the kind of thing we would need for this film.” They were looking at the books and ooh-ing and ahh-ing. Suddenly Jonathan, Ed Saxon, and Kenny all left the room for a bathroom break and when they came back about five minutes later they said, “We'd like you to do the job!”

What are you doing when a project begins?

It's all about reading the script, making notes, figuring out what the world is, and then sitting down with the director and talking about each and every scene and what kind of looks and what kind of ideas we want to present. Then I go away and come up with a variety of research and lookbooks. If it's a period film, I do research. But sometimes if it's a really intensely complicated period you hire people to do research for you. Then you sit down with the rest of the production and decide where you're going to shoot it. I'm usually the third person hired on a film.

You’ve worked on all scales of film and TV production. What are the pros and cons of smaller and bigger budgets?

Well, sometimes having too much money isn't a great thing. I'm a fan of finding really great locations for films. I love looking for them. I love finding them. I love presenting them to a director, pitching why I think it's good. There's an inherent character in a real location. Kenny Utt had a rule, which was: No building of sets unless there's an absolute necessity. On Married to the Mob, there was a scene in a huge bathtub where the bathtub overflows and water gushes everywhere. And I said, “Where are we going to do that, Mr. Utt?” And he said, “Oh damn it.”

I think that rubbed off on me, that whole concept of finding a location versus shooting [on stages]. I mean, Goodfellas had I think ninety-six locations, my God. We were moving the trucks three times a day!

The Art Department has undergone a complete digital renovation since then. Is there anything you miss?

Location scouts used to put all these incredible locations in manila folders, and they would stitch the photos together and put all the location information inside each folder. These developing places would turn the film around very, very quickly. Scouts would all sit around there waiting. The developer guy was smart enough to realize that if he could set up a room for them, they could paste all their location pictures together and he would get all their business. Later, I would flip through them like cards. If you wanted to compare them to something else, you’d just lay them all out on the table. You'd walk into somebody's office and say, “Let's look at the pictures.” You'd have the folders right there, easily accessible, without having to go on SmugMug or whatever other program exists now.

They didn't even have panoramic shots then. They would cut and paste them all together with Scotch tape. But I miss that, because when you're looking at these folders, there's just something about it. Computers in general have made this world a hell of a lot easier in so many ways — We were doing budgets for Silence of the Lambs on the standard bookkeepers accounting graph. It was just pages upon pages. And scripts, of course, were just copied. The paper load was insane. Even now, very few people draw sets with pencil. There are a couple of art directors who still do, but for the most part everybody's on CAD now.

I remember Jonathan Demme said, “Kristi, we worked during the Golden Age of filmmaking.” Because Wall Street has moved in, and they are all looking at the bottom line all over the place. The fear factor of making a film if it doesn't do well, you know, you lose your mind, or your job. All of this success stuff is really baked into the industry right now. Whereas in the old days, you could make a movie and if it didn't do well, so what? You'd make another better one.

When I did Shoot The Moon, which was a film that we shot out in Northern California, we based ourselves in Sausalito and Marin County. Oh my God, so much fun! We all had rented houses… great houses. We had crazy weekend parties. It was absolutely the best. I had been there maybe a month and we were building a house from scratch. One day, Alan Marshall, the producer, said, “Well, we just got our money.” I said, “We didn't have it before?” And he said, “No, we didn't!” That would never fly today.

We’ve just come out of this major strike. Talk a little bit about IATSE, our union Local 829, and what should be prioritized.

I don't know what's going to happen. I think that all the unions have to get together and negotiate their deals at the same time. Let's lock everybody in the same room, you know, until everything is resolved in every single aspect. Everybody — teamsters, editors, actors, directors, producers. I mean, many producers are also fed up and disgusted now. A lot of producers aren't getting a dime. It's fascinating. Producers will put a line item in the budget for themselves, but they won't pay themselves because they need every dime to make a film. I’m talking about independent films. So you make a budget: OK, it's going to cost, let’s say, a million and a half dollars to do this film. It's going to take twelve days to shoot. And they might put a line item in for $50,000 dollars, but they don't get it because they need that money to make the movie. Oftentimes independent producers don't get paid. Maybe if Netflix buys it, at that point there will be a payment for producers but by and large, producers often don't see anything.

With that said, what should the union be prioritizing right now? Workers’ conditions, number one. Turnaround times, number two. Crew hours should be tied to the actors. The actors get a twelve hour turnaround. So should the workers, so should the below-the-line people. Designers should get a piece of the action. Their designs are the reason why the film looks the way it does and the reason why the actors look the way they do, and there should be negotiated participation for people below the line. I mean, when I'm a director, I get residuals. When I did New Amsterdam, it's based on the amount of views and whether it’s international, and I get a nice little check every once in a while. I'm not a big wig, so I don’t get a lot. But I did get money because it plays in different territories. I get it because the unions have negotiated this. The Directors Guild has that in their contract.

I think this meme our friend Katie Oscar sent me says it all:

That is hysterical. It does.

What are your best skills?

I know how to talk to people. I know how to sell good ideas, and acquiesce to bad ideas. I love to collaborate. I love stories. Stories are the most important thing for me. If there's no story, I can't do it.

Is there a specific thing that an Art Department pulled off that you were proud of but that ultimately was changed or left out?

OK, to preface this: Every single film has something like this. When I was doing Revolutionary Road (Editor’s Note: Zea’s work on the film earned her an Academy Award nomination) with Sam Mendes and Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet, mostly everything was done to Sam Mendes's satisfaction. We did arrive on set one day in the office where Leo works with all these other people in cubicles, and it was a location down in Wall Street, dressed to the gills. Everything was ready to go and Sam walked in with the DP, who said he couldn't see the heads of everybody, so we have to lower the walls of all the cubicles. Oh. So at the time, I didn't say, “Can't you raise the camera up a bit to see everything?” Instead what happened was that everybody went away for lunch, and this brilliant set decorator and lead man went around to every single wall and cut down each of those partitions by three inches. So that was an easy fix.

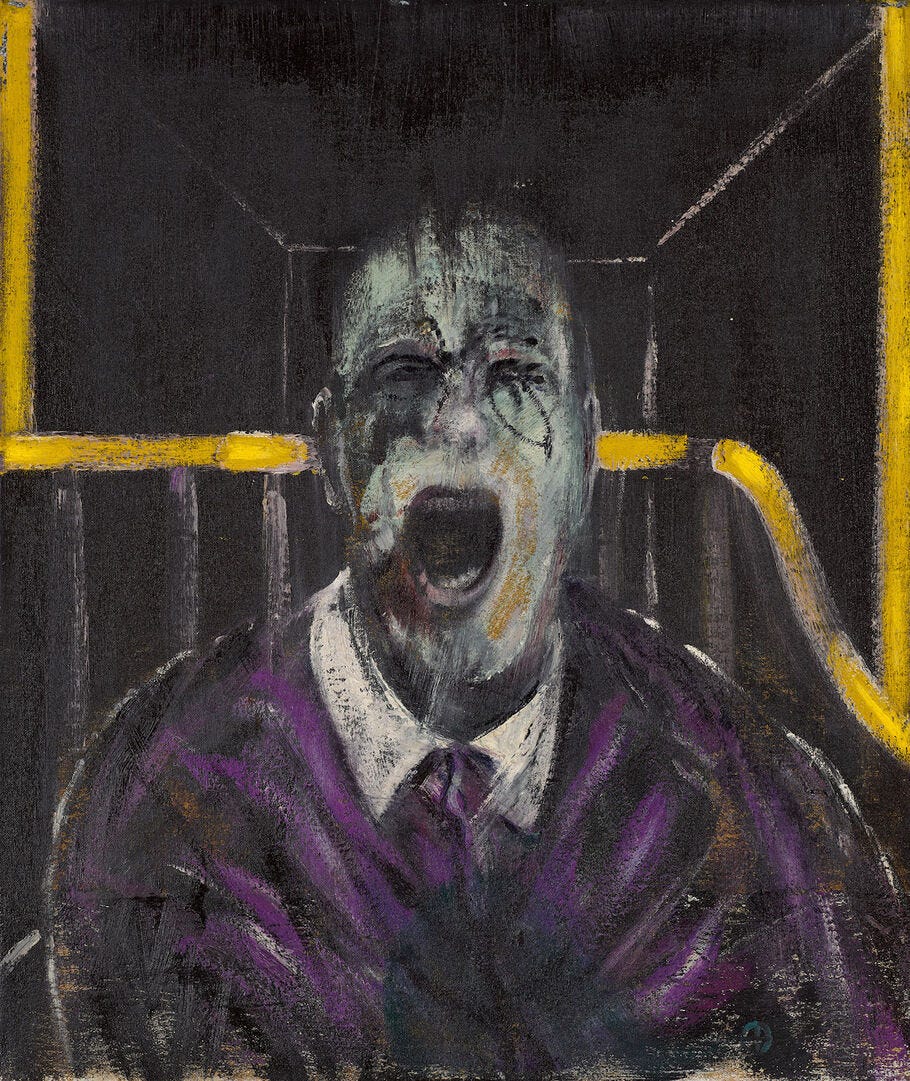

The difficult fix was on Silence of the Lambs. The scene when the police find out that Lecter has caused all this shit in his cage. They don't know that yet, they're down below, scrambling to go up the staircase to try and figure out what the fuck's happened, they open the door and there's this ghastly cage and horrible things have happened. So I went extreme. I had Karen O'Hara, who's one of the best set decorators in the world, send up a carcass of a sheep. And we splayed the carcass open so that you can see all of the ribs. Lecter had done this insanely dastardly deed and hung up this carcass of this policeman, slit him down the middle. It was all based on a Francis Bacon [painting]… God when I think about it, I'm just like, What drugs was I on? But I wasn't. Francis Bacon has a series of Pope images, they’re hideous — their faces, their teeth — and it's all done in this cage-like thing, and so I took that notion.

I just threw all this shit at it and invented this crazy installation with lighting and everything. I brought Jonathan Demme and Ed Saxon in to see it on a Friday — we're going to shoot on a Monday — and they walked into the space and they looked at it and they just turned around and walked out. I went outside, saying, “What's up guys?” They looked at me like I had lost my mind, and they were both pale and said, “People will run out of the theater when they see this.” I said, “…OK…?” I mean, I had drunk the Kool-Aid by this point. I said, “Yeah, that's right!” They were paralyzed, these two guys were quaking. Jonathan said Lecter couldn't do that in that amount of time, it's gonna pull everybody out of the film. OK, fine. So Carl Fullerton, who's a magic makeup guy said, “I've got a dummy of a body. We can hang it.” We added all his gorey innards. Lecter cut out this big huge flap, so he can eat his heart. We put the poor policeman on the outside of the cage, which I thought was even worse than what I was considering, and Jonathan said, “OK, fine.” So they did that, and that's what's in the film.

Can you talk a little bit about Michael Shannon’s brief appearance in Revolutionary Road? It’s stayed with me forever.

The scene took place in the living room. And there wasn't a whole heck of a lot that I had to do except create a container for the scene to take place in. It was in a real house with real physical limits and he was this big creature in the middle of it. Which would never have happened if I had built a set. Production designers are always thinking about Oh, the camera needs this and Oh, we have to make the ceiling open so that the lighting can come in and we have to be able to fly the walls , etc. We had none of that. That's part of what makes that scene so powerful: Michael is standing in this room, being who he is, and they are completely trapped by it. I think that's because the house had limitations. His incredible performance was highlighted in a way by the fact that this house was so claustrophobic and very, very plain in the sort of mid-century modern way.

Do you prefer contemporary or period pieces? Is one more difficult?

Just regular, modern-day stuff is the hardest thing to do, because you want to be able to impart some kind of idea and creativity to the scene, but everybody knows what modern is all about. If you're doing a fantasy or futuristic thing, you can invent more.

If you do a design that pulls you out of the film, then I consider it a failure. It could be that I'm just too sensitive to that, because I'm watching and looking and assessing that type of design very, very carefully. When I do costume design or production design, I just want it to be seamlessly embedded, making an effort to try and round out the story, give people environments that are going to help them tell the story of what's going on in their lives.

I remember Brian Morris, who's an absolutely incredible production designer I worked with on Angel Heart, told me that it was so important for him to fill out every aspect of a set for the actors, including putting things in the drawers so that if they open them there's something there. I've done that on all my sets.

The production designer’s involvement is necessary both long before and during shooting. Tell me about the costs and rewards of this career.

As a production designer I work really long hours. I get picked up in the morning here in Nyack [about 30 miles north of the city] at 5:00 AM and get driven to Brooklyn or wherever the offices are. I get to the office, and then I work until probably seven or eight o'clock at night. Then I'd be driven home, then turn around and do the same thing. Every day. I’m lucky because I have a driver. Most crew members don’t. It’s a grueling schedule.

You know, it's very hard to keep a marriage going. It's hard to be on top of things for your children. You have to find a compromise with your personal life because the film industry is so demanding when you're working on a film, in a position like I'm in. There is no alternative. You cannot just sort of say, “OK, I won't come in today because my daughter is sick.”

Once a child comes into the mix, you really have to figure out who is going to be the primary caregiver. I wanted a child desperately. I also realized that I was this working professional and my husband at the time said, “OK, we’re going to be a duo.” We were going to be production designer and art director, because he had gone to Princeton for architecture. We started to work that way on Lorenzo's Oil. Afterwards he said, “I don't want to do this, this isn't for me. I want to take care of our child. I don't want someone else to raise her.” That really changed things. Make sure that you have worked out who is going to stay home, and who is going to work. The film business is not friendly to families. When I was directing a Carson McCullers short story for HBO, my daughter had just been born. I was actually pumping my breast milk in a closet while they were doing setups. Oh my God! I'm not sure that's the right way to be a mother…

Is there a project you’re most proud of?

I always think of Silence of the Lambs because it had the depth of great storytelling and it was such a visual feast. It had incredible actors and an incredible director. I had no idea that Silence of the Lambs was going to be as big as it was. I am very grateful that I met Jonathan Demme and we could work together on so many of his films. He is sorely missed.

Charles Caster-Dudzick is a filmmaker and multimedia artist specializing in animation, scenic art, and production design. He graduated from Brooklyn College, is a member of United Scenic Artists Local 829, and has worked in NYC film and television for over a decade.

Listings

The Booger team is putting on a comedy show tonight at The Gutter in Williamsburg featuring the cast of the film, including Richard Perez, Sofia Dobrushin, Jordan Carlos, and Garrick Bernard. Hosted by Edy Modica.

All proceeds benefit NYC cat rescues.

Casting Double is looking for New Yorkers in disputes that need to be resolved and are willing to enter mediation services. For a doc produced by Darren Aronofsky’s Protozoa Pictures. More here.

Jacob Kessler is looking for unedited fiction and nonfiction short films for his students to work on at University of Iowa. Email jacob-kessler@uiowa.edu.

HBO is hiring an editor. Apply here.

Neighbors, a documentary series, is searching for unique ongoing neighbor/neighborhood disputes and interesting stories. Email HelloNeighborsTV@gmail.com.

The 48 Hour Film Project, in Montreal, is looking for teams to enter and make a film this September 20 - 22. Winner goes to Filmapalooza in March 2025 and is eligible for a spot in a screening at the Canes Film Festival Short Film Corner. $99 CAD to register. Email jasen48hr@gmail.com or erin48hr@gmail.com with questions.

If you would like to list in a future issue, either A) post in the Nothing Bogus chat thread, or B) email nothingbogus1@gmail.com with the subject “Listing.” (It’s FREE!) Include your email and all relevant details (price, dates, etc.).