Frame by Frame: 'Universal Language'

Director Matthew Rankin and writer Ila Firouzabadi break down the choices behind key images in their new film.

Universal Language, which hits select theaters Feb 12, has been twelve years in the making. It was directed by the Canadian filmmaker, Matthew Rankin, but Rankin describes it as the work of a group brain — a collaboration between him and the writers Ila Firouzabadi and Pirouz Nemati (who also stars). That the film took a long time and was a group effort makes sense when you watch it. Universal Language weaves together three stories that take place in a fictional zone somewhere between Winnipeg and Tehran, and it is packed with witty details, lived experience, clever cinematic references, a communal spirit, and lofty ideas about humanity’s relationship to places and one another.

I first caught Universal Language at last year’s New York Film Festival, and it was one of my favorite films at the festival. I was charmed by its playful humor and handmade aesthetic, but also struck by the evident care Rankin and team put into each image. Throughout the film, drab brown and beige brutalist buildings are juxtaposed with colorful expressions of humanity. Wanting to learn more about the intention and process behind different images, I had Rankin and Firouzabadi break down some of the film’s key frames.

This is basically the first shot of the movie. I wanted to ask about what this location was, how you found it, and how you figured out the blocking of the scene.

Matthew Rankin: It is a school. Schools are great to film at because they don't have any money. They will take your money no questions asked. We shot in a lot of schools because they were all built in the brutalist era and that was kind of a tuning fork for the movie. And the answer was always yes.

The classroom was in fact a lunch room. So we had to bring in a fake wall, which is the actual wall you see when we go inside. When we do go inside, it's many months later and it was shot in a studio with that same wall we see in the background. So there's artifice. A place pretending to be a place — but also a modified version of itself. And I love this. I did a storyboard and I really wanted the character to enter a door and end up in a window. I was looking for exactly this. I was hoping for something beige. It's actually very complicated for him to get from that door to this room. He had to run.

This whole scene I feel is the thesis of the movie. The frame is a brutal concrete and brick wall, and it's rigid. It's harsh geometric lines. But once he moves inside, the sound moves with him. And then a little boy is going to come in and we go back outside again. But when we go back outside again, we're hearing both outside and inside simultaneously — as if that wall doesn't exist at all. And I feel that in a way is a tuning fork for the film. We live in this very brutal era, and I think since the pandemic solitude and rigidity and binaries have become pathological. But I don't feel like our lives are like that. I feel like in politics, in social media, in our economies, we're very rigid. But I still believe our lives as humans are not like that. We live a very fluid existence of mutual dependence. So this image with its brutal wall that we move right through as if it doesn't even exist, that's what this movie's about. It is about a larger sense of belonging.

This scene makes me think of 400 Blows and so many other movies where there are unruly children and then an older authority figure who's trying to keep them in check. So I'm wondering if you think that's a universal dynamic that will always exist?

MR: I do. The biggest tuning fork for this scene is Where's the Friend's House by Abbas Kiarostami, but of course you're right. That scene is also inspired by 400 Blows, as it is inspired by the very angry school teacher in A Very Simple Event by Sohrab Shahid Saless. And the angry authority figure is a character that is with us definitely. Here, he's kind of there for comic effect. For me, the worst expression of humanity actually should be funny. I think that anger, stupidity, delusions, lust, all these things are innately funny. And these kids are kind of like that. He's angry at them but they barely react to him. And then of course the character Negin has this ironic relationship with him. This is this crazy person that she just has to deal with. We have to deal with impossible people in life, and it's better to have a sense of humor about it. This character is sort of a composite of teachers I had when I was in elementary school who really wanted to be cool and were not accepted as cool by the kids and thus became very bitter and angry and punished them. Which is innately funny to me.

Here we have this Kleenex store. Where did that come from and how did you design it?

Ila Firousabadi: We were talking with one of our friends and she told us about a ceremony that goes on in Iran. When you're going to a funeral and you’ve lost someone, of course you're crying. So it's common that people come with Kleenex and give it to you. That inspired this, and the jackpot later. And the lachrymologist who was collecting tears of everybody in the cemetery. So all these things were connected: Kleenex with tears and lachrymology. This scene is a bit surreal but it has its beauty in a very weird way.

MR: We're really interested in this space where something is so sad or disappointing that it becomes funny. That's sort of the zone that this movie is interested in. And the idea of Kleenex exaggerated to its pathological extreme — the extreme friendliness, the extreme empathy of going around a cemetery and offering people Kleenex, is something we find very funny. There's no joke in this scene structurally. Whereas a structural joke has a three act structure — here's the setup, here's the punchline, and here's the space where you laugh — this scene has no jokes like that in it. But it is a comic situation and there's always two or three people in the audience who are on the floor laughing at this. The people who find this funny have connected to it.

This I felt was such a beautiful moment of connection outside of a very brutal building. Can you tell me about why you shot this the way you did?

MR: I wanted to shoot all of these boring spaces with the same spiritual devotion that Terrence Malick would film a sunset. And sort of fill them with meaning even though they're completely devoid of it. This hug was inspired by our collaborator Pirouz Nemati, who is one of the writers and also plays the character of Massoud. This is how he hugs us. He does these really long hugs and really holds you. I'm a big hugger myself, but Pirouz will hold you for minutes. And at a certain point it becomes funny, and then it becomes really divine. So that's what we were after with this.

And also there's the Rod Peeler bench, which says: "I never sleep." He's an actual guy in Winnipeg. He has a side hustle as a Rod Stewart impersonator. And his catch phrase is, "I never sleep." I really wanted one of his benches in the film because they're all over Winnipeg. I emailed him at like 1:30 in the morning and I got an answer immediately. Which means he really doesn't ever sleep.

I'm curious about the writing process regarding sets and props like the Rod Peeler bench. Are they things you've just been collecting over the years?

MR: It's hard to delineate. I'm not sure Rod Peeler was in the script we wrote. We knew we were going to film this and it would be a wide shot. I love benches. So the idea of putting a bench there felt like another little narcotic detail we could squeeze in. But maybe that emerged during the storyboarding. Sometimes when storyboarding, my hand knows something that my brain doesn't. I'll do this image and it'll be like, "Oh, it sort of needs a bench." So often when you start to transform the script into the images these little discoveries come along.

IF: I want to add something about this shot. Matthew, Pirouz, and I always said, "OK, this is a very long hug. But in a way it's also a long embrace between Winnipeg and Tehran.” It started from a friendship, but it still goes on. It's now expanded. We're showing the movie in Tehran, Winnipeg, Montreal. So it's kind of a very long, beautiful embrace going on.

Another bench here. The tour guide is saying that the briefcase is a "monument to absolute inter-human solidarity." Tell me about that.

MR: That comes from something that happened to me when I went to Tehran actually. I went to the train station and I left my bag on a bench as I was waiting for the train. I got on the train. I went hours away and realized when I got there that I had forgotten my bag in Tehran, so I had to go back hours again. And when I got back I thought maybe there would be a lost and found. But I went back, and my bag was exactly where I had left it. Nobody had touched this bag. And I was really quite moved by this. So we exaggerated it to absolute absurdity: It's been there for forty years.

What's interesting about this too — and this reoccurs throughout the movie — is you've got these beige, brutal backdrops and then the wardrobe is very eccentric and colorful.

MR: It's true. We did think about this a lot. We wanted the constructed world to be very drab but the human world to be really alive. That is, I feel, our world. Our constructed world is infinitely intimidating and drab and rigid but our lives as people are infinitely more fluid. So we wanted to feel the exuberance of these people. It's also incarnated by the earmuffs Pirouz wears. He wears this very drab, grey outfit but there's this flourish of color in his earmuffs. So it's about that contrast: the rigid and the fluid, the drab and the ecstatic.

So here is the riel frozen in the ground. And you have this aerial shot over it where you pulled out from a tight close-up.

MR: We wanted to see the money really well. The $500 riel note was designed by a graphic designer in Toronto. It's an amazing work of art. The idea with this was to focus on the money. I wanted to shoot as little as possible. The decision with this shot was made in function of what would follow. I knew I didn't want to show Pirouz's face until the end of the scene. He would be this spectral presence until the end and we wouldn't exactly know what he meant. And then later we'd see him. So this was part of that design. We start on the money and move up. We see they're in this white expanse and then we begin to follow them. It's about following the situation. It's also a reveal. Earlier we see Nadin arrive at this spot and she finds something but we don't know what she's found. She goes off and gets her sister. She's in an agitated state. “You must follow me.” But what has she found? So this is the reveal. And then as we move up, we discover the situation that they're in.

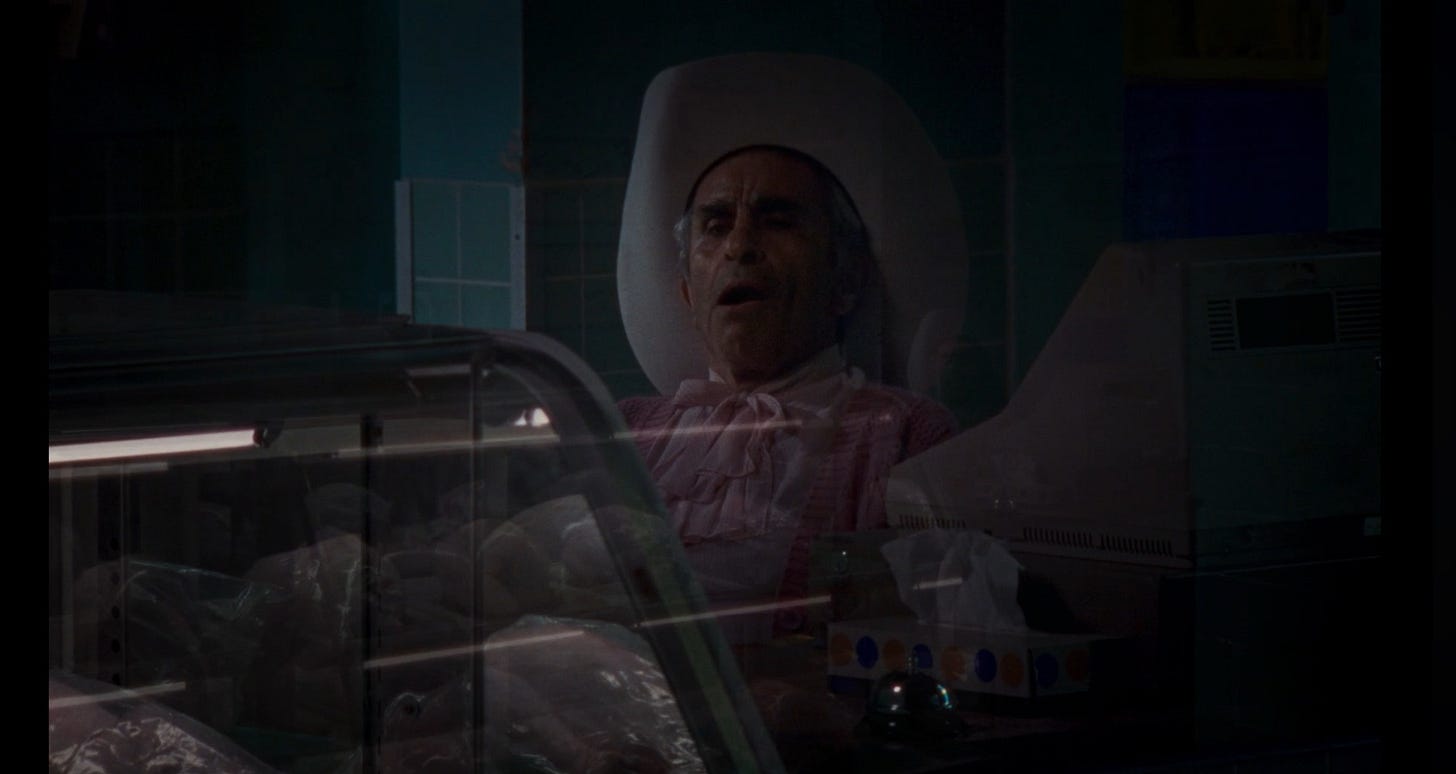

This is an amazing set, like the Kleenex store. What was this initially? How did you build it?

MR: This was a set built from scratch by Louisa Schabas, the production designer. And we knew the guy was going to be wearing pink. And we thought mint green was the right contrast for him. I love all these old places that have photos of the founders of whatever bland restaurant it is. And that's what we wanted. The board of directors are actual turkeys. And they had little name plaques underneath. Each name is a member of The Guess Who, a Winnipeg rock band. That's a little joke that Farsi speakers might catch.

IF: This green I always say is "Melancholic Green."

This is really the climax of the film. It's this transcendental moment. Broadly, could you talk about the tone here and what you wanted the cinematography and sound to make people feel?

MR: I have to say, this part of the movie is hard to speak words about. There are things you can say about a movie, but there are certain things that cinema can say and when you try to translate that into spoken language it doesn't somehow translate, and if it could you wouldn't have to make the movie. It's like that. This is a very abstract moment in the movie.

But I will say this: This part of the movie — the music in this moment — was dictated to us by the turkey man you just saw. When we shot this we had no notion of this music ever being part of it, but the turkey man came to set and he had this idea that he should sing for the turkeys. We had no idea what he was going to sing, but we were like, "Yes, let's do that." And really my only intervention was to change the lights. We thought if he's singing for the turkeys it's at night. But then he sang. He called cut when he was done. We were kind of amazed. And the poem he sang is incredible. It connects absolutely.

It's so emotional but it's coming from this guy who's dressed very silly in this very eccentric set. I'm amazed that that emotion of it translated in spite of all of that.

MR: Or, I think, because of it. I feel like those tensions reach their apotheosis at that moment. It was one of those miracles of filmmaking where you allow your collaborators to express themselves through the prism of whatever we're making together. And then our composers, Amir Amiri and Christophe Lamarche-Ledoux, constructed the entire musical sequence around this moment. The music starts much before that, but this is the music cue. It became part of the design and became integrated into the fabric of the movie.

See also:

Listings

Dark Room screening + salon returns to the Press Room at Alamo Drafthouse Manhattan tonight, Feb. 10. Doors at 6pm, films at 7pm.

Eli Barry is looking for work. Eli is a media production pro specializing in visual media and content, including work at Marvel Entertainment. He has produced award-winning short films, music videos, and commercial content. Email me@elijahbarry.com.

The Sundance Producers Lab fellowship is accepting submissions through Feb. 12. Apply here.

The Emerging Filmmakers Program is looking for female-identifying, early-career filmmakers based in Washington State. Program includes training, mentorship, paid apprenticeship, creative development, and $10K in funding for a short film.

Aaron Schoonover is a Casting Director available for your short or indie feature. Able to cast remotely out of various hubs. Flex rate sliding scale for all budgets. Experience casting on studio projects and super indie projects! Email schoonovercasting@gmail.com.

Applications are open for the Jerome NYC Film Production Grant. Deadline is April 3. Supports NYC-based early career filmmakers working in short or long form, experimental, narrative, animation, doc, or any combination of genres. Up to $30K available.

No Film School recently published a massive list of winter film grants, labs, and fellowships. Check it out here.

If you would like to list in a future issue, either A) post in the Nothing Bogus chat thread, or B) email nothingbogus1@gmail.com with the subject “Listing.” (It’s FREE!) Include your email and all relevant details (price, dates, etc.).