Video Store.Age Is Trying to Help Fix Indie Distribution

Founders Ash Cook and Aidan Dick discuss a new venture aimed at helping obscure, ambitious work find an audience.

As a programmer at Sundance, Ash Cook has spent the past eight years advocating for films like We’re All Going to the World’s Fair and Kokomo City — films with small budgets and bold visions, made by people working in the margins. Over that same period, Cook watched as the system of indie distribution increasingly failed films that were challenging and didn’t have ample resources. “There’s been a consensus for years now — between sales agents, distributors, and filmmakers — that distribution is broken,” Cook says. “I felt like: What’s one thing we’re actually going to do?”

Cook had no illusions that he was going to fix the system himself. But he did think he could help some of his favorite films that he’d seen through his programming work find an audience. “It began as a pet project: How could we get these films into the audience’s hands?”

The answer: Video Store.Age, a new company he founded with Frameline programmer Aidan Dick, which launched today. It’ll work like this: Each quarter, Video Store.Age will release a collection of five features and five shorts on encrypted USB drives. The company will launch each drive with a non-screening event (the first will be a roast of Caveh Zahedi, on February 27, at Life World). And people can buy the drives at the events or through online mail orders. Profits will be split 50-50 with filmmakers. “The scale we’re aspiring to work at is pretty modest,” Cook says. “And it’s kind of been abandoned, because people are only working on films that are going to recoup millions of dollars. This real independent space feels like there’s a vacuum right now.”

I spoke to Cook and Dick about their aspirations for Video Store.Age, the systemic problems in modern distribution, and their first slate of titles.

When you say “distribution is broken,” tell me what you mean. When did it start and how did it happen?

Ash Cook: It’s a lot of different things. It’s a confluence of issues. Streamers changed the game — coming in with so much cash and beating out a lot of boutique distributors, being able to offer MG and give people the deals they wanted up front — and that meant that they boxed out some of the people who were doing things that were more hands-on, more filmmaker focused and smaller scale, to the point where they were pushed out of the industry and it left a lot of open space there. And then, after so many years of overspending on content and realizing they had to have such a critical mass, they’re not even able to pay much money anymore. So over time, as streaming has risen and theatrical has dwindled, what’s happened is that the deals available to filmmakers are no longer consummate with their performance. So basically, to get a deal is extremely competitive, it’s very unlikely, and it’s pitiful. In an ideal world, you get a streaming deal and everyone watches your movie. But you’ve signed up for an MG that’s so low — you’re keeping maybe 200,000 people on Netflix for a month: imagine what kind of money that is. But you only get what you signed for. Or, your film gets buried on a platform and nobody ever sees it even though it’s out there.

Aidan Dick: From an insider perspective, too, there’s just not transparency in terms of how many people are watching different films. That information is valuable, and it’s being withheld from filmmakers, and it’s something we want to be able to provide them.

Why address the problem in this specific way?

AC: We see a huge appetite for the slower media movement — people feeling like they have an unprecedented access to content but not really any curatorial point of view to find a way through it. No guidance to the editorial. And the bloated feeling is hitting a lot of people. There’s this consummate decline in quality if we’re working at this quantity. So, when you follow those feelings and follow filmmakers we’re interested in working with, this idea naturally emerged to do something in a distribution space that felt more humanistic, slower, hand-to-hand, DIY, kind of punk, kind of bootleg. And surprisingly, there was tons of momentum as we started having conversations with filmmakers and other distributors. It started as a pet project, but once we realized there was momentum, we asked: How can we build a runway long enough to capitalize on all of it? So over the past eight months, we’ve brought on capital partners to back the venture and we started thinking about it as a real label.

We’re only planning on touching twenty titles in year one. The size is such that we can be hands on with each team to build a campaign that makes sense for where they are in the film’s life cycle and what they want out of our collaboration. For example, for films that are on our slate that will also be in theaters, we’ll be selling drives in the lobby, like you would at a punk show where you’re getting merch as you leave. For films that are older, we have a different strategy. For films that have a great band that scored it, we have a different strategy. A huge part of the model is that bespoke element. As a festival, as a distributor, this process of trying to standardize and fit everything through the same mold is just not working. These are each precious, specific materials, and we’re planning to be really responsive to that.

AD: The thing that attracted me to Ash’s idea at first was talking about these in-person events, and how we both feel let down by just having a Q&A. You’re physically so close to a person who made something you loved, but there’s not enough time or space to get into anything about it. So I liked the idea of creating these ancillary, curated events around the films, where people can find their own way into something and take away that film and that experience and go home and watch it with their friends.

AC: We want to create as many opportunities as possible for people to find their way to this media. Maybe you know the director, maybe you know us, maybe you know the venue. And then you become part of something that feels rhythmic and social and connected. And the events will act like primers. We’re not planning on working on any films that are too commercial, so there’s a challenge. These are tough movies, they’re weird, they’re interesting, they’re different. So giving people a chance to set the table a little bit with their audience and give them a primer before a watch rather than a 20-minute explainer after will be valuable.

Were there certain films you had in the back of your mind as being Video Store.Age films? And if so, what connects them?

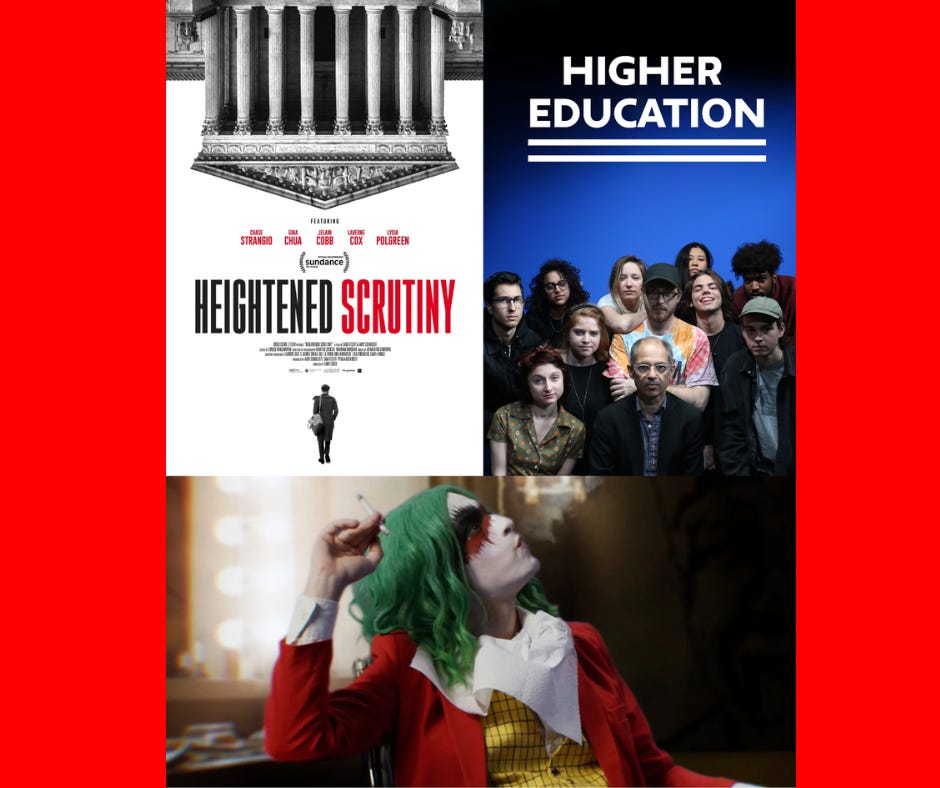

AC: I’ll give you three from our first collection that are indicative of the three main editorial thrusts we have. We’re going to do Sam Feder’s new documentary Heightened Scrutiny, which we world-premiered at Sundance last year. That is indicative of one thing we want our drives to do — circulation of revolutionary materials. When we’re talking about the collapse and narrowness of the distribution landscape right now, there is a big political implication. We’re seeing a situation where if the only way for filmmakers to get their bag is to get in bed with Bezos, that’s not A) good, and B) it’s not the kind of platform that’s going to provide the opportunity for films that aren’t politically in line with their agenda. That’s a big deal. I think people don’t realize how these things have come to really serious focal points. The Murdoch family are majority shareholders of Tribeca, Penske Media owns SXSW, the channels are in the hands of very few. So what is an independent channel right now where you could have 1-to-1 digital ownership?

And then, we’re going to collect The People’s Joker. We’re going to have a digital exclusive of the VHS copy. And that’s expressive of the hope that we’re going to be circulating things that have this mythology. If you’re down an r/lostmedia thread and wondering how you can see something, we want to help get it to you.

Third, we’re going to do Caveh Zahedi’s Higher Education. And that’s indicative of films that have made it out in the circuit, but in their time in the cycle never hit a distribution groove and aren’t available — things people know about, talk about, but are under-seen.

How would you each describe your tastes?

AD: I think the films that I’ve really loved over the past couple years are movies that feel like the community they’re creating around and the community they’re creating inside of the filmmaking world feels like an ecology they’re growing and wanting to continue. That’s something Ash and I talk about a lot — wanting to align with people putting their energy in that direction and who are excited to work with us or finding new ways to share their work. I also love weird, sad, scary documentaries.

AC: One of the best parts of programming is how expansive your tastes can become — and how you learn there’s an audience for every film. Flexing those muscles and figuring that out is really fun. But the films that lie closest to home for me are low budget, grimy, gritty, and bold. I was really attracted to Sundance for filmmakers like Gregg Araki and Jennifer Reeder, who were working on these shoestring budgets but doing things that are so provocative, powerful, interesting, and bold.

The films I’ve been proudest of bringing into the fold at Sundance have been on that tip. I think of We’re All Going to the World’s Fair and Kokomo City — these smaller films that I’ve been so excited to be able to get into the program at Sundance. How I’d express my taste is it’s mostly people who are working on the margins. So there’s this existential question at Sundance when you’re bringing marginalia out into the mainstream. It sometimes withers in the sun. I’m thinking infrastructurally about how you work at the margins and stay at the margins, because that’s where shit is cool and stays that way. And that’s what we’re doing here. We want it to be sustainable without making compromises about what that means for the editorial.

What will the first launch event look like?

AC: The first event will be on the 27th of February. We’re going to host at LifeWorld in Brooklyn, and it’ll be The Roast of Caveh Zahedi. I think it’s a good illustrator of what we’re doing. These events are exclusively non-screenings. Theatrical is so important, but there are so many great collaborators out in the field who are doing that work. We don’t need to be competing with that. We don’t need to be cannibalizing our own filmmakers’ audiences. We want to be doing something that feels more like nightlife or a literary reading — something profoundly social and a little less intense as an audience member. So we’ll have a lineup of some sceneyboppers who are going to come and roast Caveh at LifeWorld, and you’ll get the drives at the event. Maybe Caveh will tape the roast and put that on the drives that we sell online afterwards. The drives are fun because they’re so dynamic. They can take so much new material. We’re working with every team to put bonus content on each release. This is one that feels really organic.

How will you find titles down the line? Can people submit their films?